In this interview, Singing Dragon author Lisa Spillane answers some questions about her new book, Six Healing Sounds with Lisa and Ted: Qigong for Children, which teaches young children how to transform negative feelings into positive ones by using simple breathing techniques that are based on ancient Chinese Qigong exercises.

In this interview, Singing Dragon author Lisa Spillane answers some questions about her new book, Six Healing Sounds with Lisa and Ted: Qigong for Children, which teaches young children how to transform negative feelings into positive ones by using simple breathing techniques that are based on ancient Chinese Qigong exercises.

Tell us about your background and your experience of Qigong.

While I’m thankful for the many happy times I enjoyed as a child, it’s mainly the challenges I faced in my early years that have led me to write this book. I was born in New York and lived there until my father died shortly before my eighth birthday. After that we moved to Ireland where my parents were from. My father died from a brain tumor which he suffered with for two years, and the trauma of that and subsequently moving to a new and very different country was a lot to deal with for a little girl. In time, those experiences gave me a desire to pursue a career in education with the aim of helping children to express themselves.

I qualified as a Teacher of Art and Design, and for my Master’s Degree in Education I researched and developed programs for children from at-risk backgrounds and for young offenders. Nearly twenty years ago, along with two artists, I co-founded Artlink, a charity located in the Northwest of Ireland that provides opportunities for people of all ages and backgrounds to learn and experience art. My childhood experiences coupled with what I’ve learned through teaching have reinforced my view that children need to be taught techniques to manage their emotions so they can develop lifelong habits to protect themselves from the consequences of stress.

I was introduced to Qigong meditation by attending classes taught by Grandmaster Mantak Chia three years ago. Since then I’ve continued to learn through local trainers in Brussels, where I live, and through self-research. The first time I did the Inner Smile and Six Healing Sounds meditational exercises it occurred to me, when I was being shown how to rub my liver, that previous to that moment I hadn’t given much thought to its location. My organs were like abstract objects that I was connected to on a very superficial level. And, it dawned on me how ridiculous it was that even though I’d had this body for so many years and took an interest in health and nutrition, I was unable to confidently point to my spleen, pancreas or liver. I thought to myself that if I’d learned these exercises as a child, not only would I have known more about my body but I’d have been able to help myself in those dark times when I felt pushed and pulled by my emotions. Qigong techniques can help children to understand their emotions better and to have more control over them by showing them that they have the power to transform negative ones into positive ones through utilizing the body-mind connection.

What are the Six Healing Sounds and where do they come from?

This book combines the Six Healing Sounds and the Inner Smile Qigong meditational exercises. Qigong is a form of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The exercises were developed thousands of years ago in China to help people to purge toxic negative emotions from their bodies. Doing them combats the dangerous effects of stress by activating the body’s own healing systems through a combination of: deep breathing, smiling, touch, gentle movements, sound vibrations and positive thoughts. Many of the elements we do instinctively, which is how the doctors of ancient China became aware of them. They created the healing sounds from observing the noises (sighs and groans) people make for different ailments because they realized that these sounds cool and detoxify the body’s organs. In the practice, each organ has its own healing sound, color and set of positive and negative emotions. Also, each organ has a season and associated elements. For example, the season for the liver is spring and its element is wood. To avoid information overload, I’ve only suggested the seasons and elements through the stories and illustrations so that children can absorb them with less effort.

This book combines the Six Healing Sounds and the Inner Smile Qigong meditational exercises. Qigong is a form of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The exercises were developed thousands of years ago in China to help people to purge toxic negative emotions from their bodies. Doing them combats the dangerous effects of stress by activating the body’s own healing systems through a combination of: deep breathing, smiling, touch, gentle movements, sound vibrations and positive thoughts. Many of the elements we do instinctively, which is how the doctors of ancient China became aware of them. They created the healing sounds from observing the noises (sighs and groans) people make for different ailments because they realized that these sounds cool and detoxify the body’s organs. In the practice, each organ has its own healing sound, color and set of positive and negative emotions. Also, each organ has a season and associated elements. For example, the season for the liver is spring and its element is wood. To avoid information overload, I’ve only suggested the seasons and elements through the stories and illustrations so that children can absorb them with less effort.

Why are they so beneficial?

Although the exercises are simple and easy to learn, there are many complex scientific reasons for why they work. A good number of those reasons have only become evident to us in recent years through advancements in brain scanning which, for example, has proved that smiling, even when we don’t feel like it, produces endorphins in the brain which help to reduce stress and support the immune system. Neuroscience has also shown that thoughts of gratefulness and appreciation calm the nervous system and protect the heart. We instinctively know that using the breath to calm down is very effective. And, deep breathing also increases the amount of oxygen rich blood in the body which is needed for energy and healing and it boosts the lymphatic system helping it to get rid of toxins.

Is there a “right way” to do them?

There are many variations to this practice. This book demonstrates the exercises I learned from Grandmaster Mantak Chia. I’ve tried others but these are the ones I prefer. That said, I felt it was necessary to make some alterations so they’d be more accessible for children. In the second story I chose to refer to just the stomach, even though it should be the stomach, spleen and pancreas because I didn’t want to overwhelm young readers with too many new words. And, it’s good for them to focus on the stomach at this stage in their lives because there’s so much temptation for children to comfort themselves through eating junk food. This gives them an alternative to trying to numb their feelings of worry with food. I’ve also made alterations to the Triple Warmer exercise. This exercise doesn’t relate to a specific organ, but because it aims to even out the body temperature by bringing hot energy down from the head and cooler energy up from the feet it made sense to me to describe the hot energy as the chattering, busy thoughts in the brain. The exercise ends with Ted resting his hands on his stomach which is roughly the Dan Tian area, which relates to this exercise.

For readers who’d like more clarity regarding the sounds: “haaaww” rhymes with “saw”, “whooooooo” is like the sound an owl makes except longer, “sssssssss” is like the sound a snake makes, “tchewwwww” is like a sneeze sound “achoo” except made slowly and without the “a”, the “shhhhh” sounds like you’re telling someone to be quiet and finally “heeeeee” rhymes with “pea”. And, although you should try experimenting with the volume it’s recommended that the sounds be made softly and slowly.

It’s best to do all the organs in the order they are shown in the book, making the sound at least three times for each one, but you can concentrate on just one or as many as you like as long as you do them in the right order. The more you do this the more you will make it your own. If you get caught up in trying to do it perfectly then you won’t get the most out of it. There are also postures and movements as well as other emotions for the organs to be learned but what’s in this book is more than enough to make a good start with. Learning this practice should be seen as a continuous lifelong process that taps into our inherent abilities to heal ourselves.

Undoubtedly we could all gain something from these exercises – why did you decide to write it for children?

There’s an abundance of information on the internet and many excellent books and videos that teach adults how to do these exercises but from what I see there’s very little on the subject for children. Firing up the imagination with colors and beautiful imagery, smiling and making different sounds are all things I knew would appeal to young readers and the earlier we can learn tools to deal with our emotions the better. The format of a children’s picture book is a great learning tool because it allows for a lot of the information to be presented visually. When we use our eyes to dart around the page to look at all the different elements it helps the brain to create meaning and record images, thoughts and feelings together which in the future help us to remember the sequence of the exercises with all the associated information. And, I think many adults will find through the experience of sharing the book with children that they’re benefiting from the practice too.

How do you use these exercises in your own life?

I try to do the practice daily, either in the morning to give me energy and optimism for the day ahead or before bed as a way of clearing out all the emotional garbage that I’ve collected over the course of my day. More significantly for me though are the benefits I gain from weaving the Healing Sounds into all aspects of my life. For instance, I’ve recently taken up yoga, so when I’m doing a pose that works on, for example the kidneys, I’ll smile and breathe in peace, imagining deep blue calm water filling them and then I’ll make the “tchewww” sound as I breathe out my fears. Or, if I’m confronted with any kind of a challenging situation, I’ll take a moment to smile, breathe, connect to the relevant part of my body and if I happen to be in a public place and don’t want to draw attention to myself I’ll imagine that I’m making the sound as I exhale. I find it helps to stop the stress cycle. Simply smiling, breathing, being aware of what my body is telling me and being positive instead of negative helps to put me back in control of the ship, as it were. Also, if I become aware that I’m worried about something I’ll smile and gently rub my stomach, spleen and pancreas and that helps to calm me down as I try to think rationally about whatever it is that’s bothering me.

Essentially it’s all about making a loving connection to oneself and others. When I’m outside taking nature in, I’ll look at the leaves on the trees and connect with my liver and think about filling it up with generosity and kindness. It’s a great way to quieten the “monkey mind” – to stop negative self-talk and instead bring thoughts of appreciation and joy into the mind and body.

Spiritually it’s been good for me in many ways. For example, when I’m praying I usually begin with a few cleansing breaths and making the “haaaww” sound I’ll think about my heart, release any resentments in it and then fill it up with loving attitudes. And, like Ted in the story, when I have trouble sleeping I make the “heeeee” sound and push all the noise from my head out of my body so I feel more relaxed and ready for sleep.

What do you hope readers, including parents and teachers, will gain from the book?

When my son Dualta was a little boy, it was usually when I was reading him a bedtime story that he would decide to tell me about the ups and downs of his day. Mindful of this need to “offload” at bedtime, I’ve written the stories short enough to give children the space to bring up any negative feelings that may be troubling them. Also parents can choose to just concentrate on one or two stories depending on what particular emotions are raised. For example, if a child is grieving over the loss of a pet it might be more appropriate to just do the lungs and the heart. Using this book as a guide, it’s my hope that readers are led through a process which soothes away troubling emotions so they feel calm and ready for a good night’s sleep.

Teachers can use this book to encourage children to learn about their bodies and to consider how their attitudes and behavior effects themselves and others. Learning through stories is a fun way for children to absorb information and they can relate the scenarios to challenges they face in their own lives. It can be used to prompt children to share their experiences and in so doing they will learn that emotions and feelings are a natural part of life and common to everyone. More importantly, the exercises will help them to see that they can learn ways to manage their emotions and cultivate a sense of peace within themselves.

*Singing Dragon is an imprint of Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Copyright © Singing Dragon 2011.

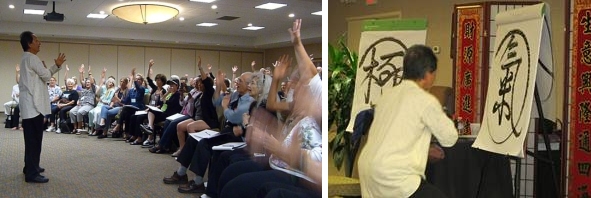

Singing Dragon was thrilled to attend the 16th annual conference of the National Qigong Association (NQA) in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, USA, from August 19-21.

Singing Dragon was thrilled to attend the 16th annual conference of the National Qigong Association (NQA) in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, USA, from August 19-21.

Michael Davies

Michael Davies

Singing Dragon received the Gold prize in the Enlightenment/Spirituality category for

Singing Dragon received the Gold prize in the Enlightenment/Spirituality category for

In this interview, Singing Dragon author

In this interview, Singing Dragon author