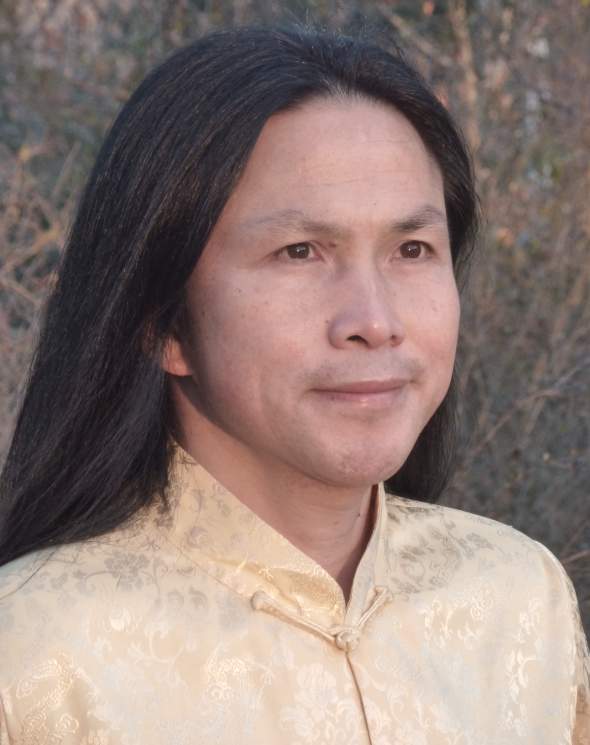

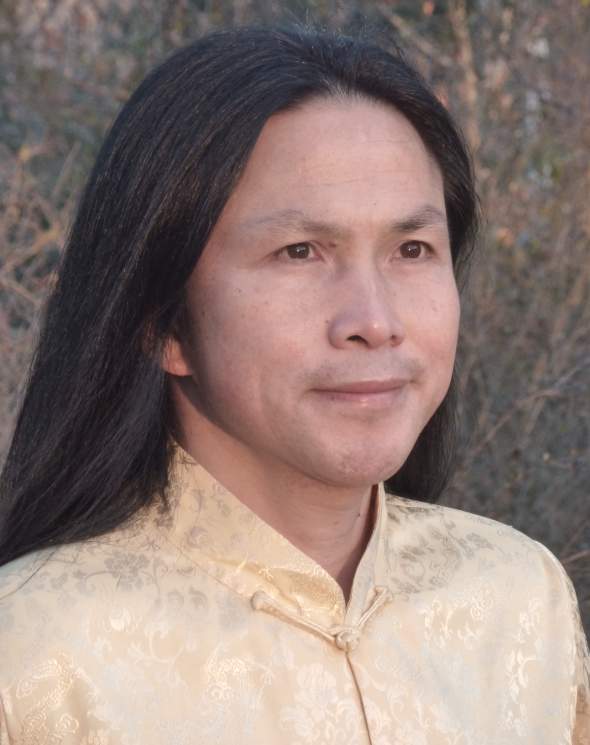

Master Zhongxian Wu is the lineage holder of four different schools of Qigong and martial arts. While in China, he served as Director of the Shaanxi Province Association for Somatic Science and the Shaanxi Association for the Research of Daoist Nourishing Life Practices. He has now been living and teaching in the West for just over ten years, and in February 2012 will visit the UK for a series of lectures and workshops celebrating the new Chinese year of the Water Dragon.

Master Zhongxian Wu is the lineage holder of four different schools of Qigong and martial arts. While in China, he served as Director of the Shaanxi Province Association for Somatic Science and the Shaanxi Association for the Research of Daoist Nourishing Life Practices. He has now been living and teaching in the West for just over ten years, and in February 2012 will visit the UK for a series of lectures and workshops celebrating the new Chinese year of the Water Dragon.

We are honoured to publish this special extended interview with Master Wu.

Master Wu, thank you so much for agreeing to talk to Singing Dragon. I think you have just celebrated ten years of living in the West. Have you found over that time that our understanding of Chinese medicine has changed?

The Western understanding of Chinese medicine has definitely changed in the last ten years. I have noticed two main changes, with respect to the general public and the practitioners themselves. In terms of the general public, more and more people recognize the efficiency of Chinese medicine to meet their health care needs. More people are embracing Chinese medicine treatments because they want minimal unwanted side effects (or better yet, none at all) and also want to build up their health in order to prevent a future illness. In terms of Chinese medicine practitioners, I have seen that more practitioners are looking to understand the roots of Chinese medicine, and are emphasizing their own personal cultivation (for example through meditation, Qigong practice, studying the Yijing, Chinese astrology, etc.) to help them deepen their knowledge of Chinese medicine. Also, I see more practitioners are educating their patients about how important it is to strengthen their own Qi by improving their daily lifestyle habits and having a commitment to some internal cultivation practice.

How can Western practitioners best prepare themselves for studying Chinese medicine?

In terms of studying Chinese medicine, there is no difference in preparation for a Western practitioner or an Eastern practitioner. The best way to prepare is to do personal cultivation. In the Chinese medicine traditional education system, before the Master teaches you anything about medicine, they always first stress that you learn to be a good person and to cultivate your virtue. A good doctor first needs to be a good person, and have a good heart to help others. Traditionally, you didn’t learn medicine as a business venture to make tons of money. For the Master to share knowledge with you, he/she has to be clear that your deep purpose and drive is to help others. The HuangDiNeiJing (the Yellow Emperor’s classic text of Chinese medicine) emphasizes that you have to be careful not to teach certain skills to the wrong person – the wrong person, meaning someone who does not carry a high level of virtue.

You are lecturing at the Confucius Institute in London in February on the topic of Qigong as the basis for Chinese medicine. Can you say a little about why this is such an important topic?

Yes, Qigong is the source of Chinese medicine. The whole system was discovered by ancient enlightened beings who made profound connections about their bodies and Nature while in heightened Qigong states. According to the QiJingBaMaiKao (Investigations into the Eight Extraordinary Vessels), a book by the Ming Dynasty’s famous herbalist LiShiZhen’s, the subtle energies of the inner pathways of the body (for example the pulses, the points, the meridians, and even the organs themselves) may be seen only by those who cultivate Fan Guan (literally, ‘reverse observation’), or the ability to look within with clarity. LiShiZhen concluded that only high-level Qigong practitioners could see the meridian systems. Before the modern term Qigong became popularized, all Qigong cultivation practices (including seated meditation) were known as Guan, which itself means ‘observe or observation’, and implies self-observation.

Also, to develop an appropriate herbal formula for someone requires an understanding of Qi harmonization. Chinese herbal medicine was first taught by the ancient shaman king ShenNong (Divine Farmer). Actually, the first Chinese book of herbal medicine, ShenNongBenCaoJing is named after him and it is generally accepted that he wrote it as well. Our legends say that, through tasting the herbs, he was able to feel the different quality of Qi in each herb and understand how it relates to the Qi of the organ and meridian systems in the body. This kind of sensitivity and awareness was possible because he was a very high level Qigong practitioner, and was able enter into heightened states of consciousness and perception.

There would be no Chinese medicine without the ancient shamanic Qi cultivation practices of Qigong.

Would you tell us a little more about Qigong? Many people in the West are confused about what it is.

Qigong is modern, popularized term for an ancient method of physical, mental and spiritual cultivation. It can be translated into English as Qi cultivation, spiritual cultivation or working with the Qi. By the way, by Qi, I mean the vital energy of the universe that keeps everything alive. Qigong practice models a harmonious way of life and has been used throughout thousands of years of history by those who wish to attain Enlightenment.

Qigong involves working with the three parts of the body (Jing, Qi and Shen). In Chinese, Jing means essence and represents the physical body. The physical body is our structure and our container. It holds our essential life energy, our Qi body and our spiritual body. We can strengthen our physical bodies by practicing special Qigong postures. As I mentioned before, Qi translates as vital energy of the entire universe, including of course, the vital energy of your body. Your breath is deeply connected with the Qi body. Qi can also be translated as ‘vital breath’. In Qigong, we cultivate our Qi body by maintaining awareness of our breath and by learning techniques to regulate our breath. This will increase our vital energy or life force. The Shen means spirit, and represents our spiritual body. In general, our mind is related to our Shen. Once we pay too much attention to the external world or worry too much about what is going on in our life, we weaken our Qi. If we are always looking outside, we leak our spiritual Qi. In Qigong practice, we learn to look within in order to preserve our life energy.

How does it relate (if it does) to practices such as Yoga?

I have never practiced yoga, so I don’t have the personal experience to be able to talk about how it relates to Qigong. However, a number of my students are yoga practitioners by profession, and many of them connect their Qigong practice with their yoga practice. They have found that elements of their Qigong practice complement their yoga practice so that in general, the practices enhance each other.

What is the purpose of your cultivation/Qigong practice?

From the view point of Daoist practioners, the Daoist tradition is the immortal tradition. The purpose of Daoist cultivation practices is to become immortal. This often begs the question of what exactly is meant by immortality. In Chinese, the word for immortal is Xian, which is an image of a person who lives on a mountain. Throughout history, many Daoist masters have referred to themselves as ShanRen– Mountain People – because they spend long hermitages in the mountains (or anywhere in nature), cultivating their true humanity. Another word for immortal is ZhenRen– real or true human being. From the Chinese ideograms, we can see that the concept of an immortal is of one who has cultivated good health, happiness, and humanity and embodies these qualities in everyday life.

The idea of immortality or everlasting life has nothing to do with yearning to live forever. On a superficial level, of course no living being can escape death. Death is simply a part of the universal Five Elements natural cycle. However, death is always accompanied by the process of rebirth. In this way, there is no death. In the Immortal’s tradition, we have an expression – XinSi ShenHuo, which translates into English as “allow your heart to die so that your spirit will live.” I interpret this to mean that by embracing death and bringing it gracefully into our hearts, we understand the knowledge of immortality. This, to me, is enlightenment.

Yes, our lives are short – no matter how long we live, compared with the long stream of the time of the Universe, our lives are just a momentary sparkle. Sometimes, when people physically die, their spirits remain very much alive. The quality of our lives is not measured by the time we spend in this world, but how we learn to transform our personal emotional energy into a force that can help others.

You are also teaching a couple of workshops in the UK in February. They sound very interesting – can you tell us a little more about the practices?

Of course. I am excited to be teaching Fire Dragon Qigong in London and Five Elements Qigong in Oxford. Both are traditional Chinese Qigong forms.

Fire Dragon Qigong embodies the spirit of the rising dragon, which is an auspicious symbol of transformation in Chinese culture. Regular practice of this form establishes free flowing Qi in the 12 meridian systems of the body. It also helps transform areas of stagnation, thereby bringing the physical and emotional bodies into a balanced state of well-being. Actually, according to the Chinese calendar, the year of the Dragon begins on February 4, 2012. I will teach Fire Dragon Qigong that same weekend in honor of the Dragon and the great global transformation that will happen in 2012.

The Five Elements theory lies at the heart of classical Chinese philosophy and healing principles and is the foundation of Chinese cosmology and Chinese medicine. The Five Element Qigong form helps harmonize the Five Element’s Qi in our bodies and organ systems with the Five Element’s Qi of the Universe. Regular practice will help us smoothly navigate change in our lives.

What in your view are the greatest benefits of practice for people looking for a healthier lifestyle?

In the traditional Chinese healing system, the definition of medicine is something that embodies these three qualities: vitality, joy and harmony. Anything may be considered medicine, and doesn’t necessarily have to be a physical object. Instead, medicine is any object, event, thought or action that increases your vital energy, brings you joy (that you then can share with others), and helps you live harmoniously with yourself, with your family and friends (and society as a whole), and with Nature. In Chinese tradition, we consider Jing, Qi and Shen to be the best and most important medicine in the world. The greatest benefit of a regular Qigong practice is that you learn to access and optimize your own best medicine within – your Jing, Qi and Shen – to support your daily life.

Does a knowledge of Chinese medicine increase the benefits of Qigong?

Yes and no. In my experience, everyone who has a regular practice of a traditional Qigong form receives benefits from their practice. In ancient times, Chinese medicine was discovered through the practice of Qigong, and it gave a pathway of understanding the Universe through each individual body. In this way, the benefits of Qigong practice precede formal knowledge of Chinese medicine itself. In modern days, we often go the opposite direction, and use prior knowledge of Chinese medicine to help guide the practice. People who have taken time to study Chinese medicine may have a better idea of the specifics of how the Qigong form is working in their bodies. In spiritual cultivation practice, there is a phenomenon called “knowledge stagnation”, where having a lot of knowledge and thinking too much about what you think the practice will do becomes an obstacle to experiencing what is actually happening. On the other hand, advanced Qigong practitioners can use their knowledge of Chinese medicine to really deepen their practice. Either way, as long as you continue your daily practice with an open heart, Qigong will improve your health and deepen the relationship you have with yourself and with the Universe.

You have for some years been teaching an interesting Lifelong Learning programme, where students spend several days on retreat learning intensively from you. Could you tell us a little about this, and about the change and development you see in the students that follow through the programme?

In China, the traditional relationship between the student and Master is like parent and child, so that the Master can continue to give students guidance and support through their lives. Also, in different stages of practice of even the same Qigong practice, students will experience different phenomena, some subtle and some strong. Having step-by-step guidance helps the students understand the changes and keeps them from getting discouraged.

The purpose of the Qigong lifelong training is to create a family-style community of practitioners who are dedicated to supporting each other in their cultivation practice. We meet annually to share our experiences with the practice and to learn how to go deeper on this path to Enlightenment. Our intensive, week-long retreats provide the opportunity to learn a form in such a way that the practice becomes a part of the students, a part of their body and a part of their spirit, and this makes it easier for the practice to become part of their daily life. The retreats offer a different level of experiential learning than a few hours’ workshop or a weekly class can provide.

Over the last ten years of teaching in the West, I have seen many changes in my students – recovery from a disease process, increased energy, strength and flexibility, uplifted spirits, better relationships with others, healing practitioners who report greater success with helping their patients, etc. It is always nice for me to see how close my students grow towards each other during the retreats and how friendships grow into relationships that feel like family. We enjoy having a big Qi family!

Is Qigong a practice in which progress for all students occurs at roughly the same rate?

Not really. Different people have different bodies, different health conditions, different commitment levels (in terms of daily practice) and so have different experiences with their Qigong practice. Even the same person will have different experiences with their Qigong practice. Sometimes you will experience areas of plateau before you reach the next level, sometimes you will feel like you are moving ‘backwards’ in your progress and suddenly shoot forward, and sometimes it is just steady. After almost 40 years of practice, I feel I learn something new from my practice every day, even from the same form, again, again and again.

Would you tell us a little about your own experience with Qigong? How old were you when you began to practice?

I started to try some Qigong practice when I was about five years old, and began to take my practice really seriously when I was about 11. Originally, I practiced Qigong to have some fun. Surprisingly, I discovered many health benefits through the practice. In my first years of my memory, I was very sick, and every week I would have a terrible fever and my parents would take me to the hospital for medicine. I realized that I didn’t have to use medicine to recover when I was 11, and recovered through my Qigong practice even faster. So, I decided to stop taking any medicine and dedicate myself to my Qigong practice. Also, when I was young, I was very nearsighted and needed glasses. One summer break, I spent about one month in nature, practicing Qigong. At the end of the month, my eyesight improved so much that I didn’t need glasses anymore. Anytime I am feeling sick, have low energy, or something in life happens that affects me on the emotional level, I always practice Qigong and it helps me recover quickly.

Did you find it hard to keep up the practice during your education years, and how did you manage it?

Not at all. I followed the traditional way, as taught by my Masters, and got up early, at 4 am, to practice at least 2 hours every day. I lived on-campus during high school and university, and would be done with my practice before anyone else had gotten up. I always felt like I had more time to do everything I wanted than my classmates did. I think I had more energy than everyone else because of my Qigong practice.

Do you go back to China to visit the Masters who taught you?

Yes. Almost every year I go to China to see my Masters and spend time with them. It is the same way I go to visit my parents, just like family.

I know you are the lineage holder of several lineages. Would you tell us a little about what this means, and how the lineage holder is chosen?

In China, traditional arts and disciplines are passed on through a discipleship system. In this system, the acknowledged Master of a given discipline teaches a small circle of students. Traditionally, the Master will always design many obstacles for the students, making it difficult to continue studying. Most students will drop off because of these obstacles. When the Master feels the time is right, he/she will select the next “lineage holder” from the close-knit circle of students who have had the perseverance to carry on. The lineage holder is then responsible for preserving the entire system of knowledge and passing knowledge to others.

Your beautiful calligraphy appears on the covers of your books – would you tell us a little about the relationship between Qigong and calligraphy?

Calligraphy is a form of Qigong — it is movement within the brush and painting with your breath. When we practice calligraphy, we are working with our three treasures, Jing, Qi and Shen, which is the same as any Qigong practice. When we make a piece of art, we need to have the same three elements found in all traditional Qigong forms – correct posture, breathing and visualization techniques. In fact, in the Daoist tradition, we use the calligraphy brush as a tool for healing and spiritual cultivation. One special kind of calligraphy created by a Master is used as talismans for healing and for FengShui purposes.

It seems it all connects up – Qigong, Healing work, Calligraphy, Qin music, Yijing prediction, FengShui. Do they all support one another?

All of these are different styles of Qi arts and Qi cultivation. These practices are Qi vehicles for human beings to connect to Nature and live in harmony. On a superficial level, these practices may seem different or unrelated, but yes, they do connect up. The entire Universe is like an invisible Qi web, which connects everything. As LaoZi states in his DaoDeJing, the universal web is vast, and nothing can escape from it.

Master Wu, thank you so much for answering all these questions. We truly appreciate it, and the Singing Dragon in London is really looking forward to your visit in February!

Please visit Master Wu’s website at www.masterwu.net to find out more about his visit to the UK in February 2012 as well as his writing, teaching, music and calligraphy. You can find his four books published with Singing Dragon – Chinese Shamanic Cosmic Orbit Qigong, The 12 Chinese Animals, Seeking the Spirit of the Book of Change, and Vital Breath of the Dao, as well as his DVD Hidden Immortal Lineage Taiji Qigong – on the Singing Dragon website intl.singingdragon.com

Copyright © Singing Dragon 2012.

Make Yourself Better

Make Yourself Better

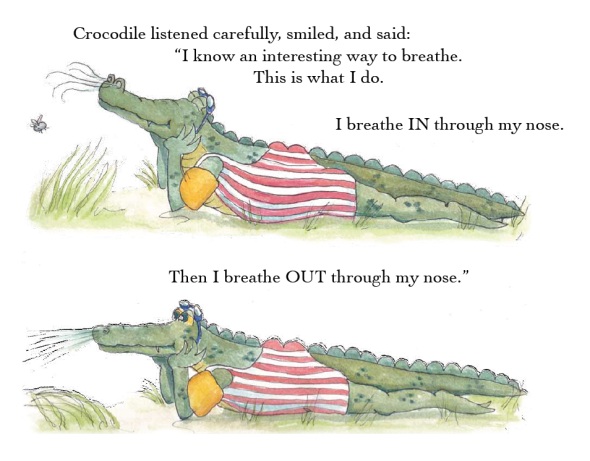

Can you tell us about your collaboration with the illustrator,

Can you tell us about your collaboration with the illustrator,

Singing Dragon was thrilled to attend the 16th annual conference of the National Qigong Association (NQA) in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, USA, from August 19-21.

Singing Dragon was thrilled to attend the 16th annual conference of the National Qigong Association (NQA) in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, USA, from August 19-21.

Michael Davies

Michael Davies