Richard Bertschinger is a practising acupuncturist, teacher of the healing arts, and translator of ancient Chinese texts. He studied for ten years with the Taoist sage and Master, Gia-fu Feng. He talks to Singing Dragon about his groundbreaking translation work, ‘the oldest book in the world’, and having all of Chinese medicine in your pocket.

Richard Bertschinger is a practising acupuncturist, teacher of the healing arts, and translator of ancient Chinese texts. He studied for ten years with the Taoist sage and Master, Gia-fu Feng. He talks to Singing Dragon about his groundbreaking translation work, ‘the oldest book in the world’, and having all of Chinese medicine in your pocket.

Thanks for agreeing to talk to us, Richard, about your five books. I wondered if you could tell our readers something briefly about each and how they came about?

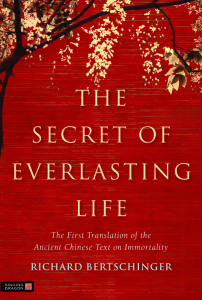

Well these books are really a summation of my Taoist studies over the last thirty years. The titles are worth repeating: The Secret of Everlasting Life, Yijing: Shamanic Oracle of China, Everyday Qigong Practice, The Great Intent and Essential Texts in Chinese Medicine. I was fortunate to meet a Chinese-American Giafu Feng in the ‘seventies who introduced me to the Chinese world of the Tao – really it was from Giafu that I got the inspiration for this work. He was brought up in Shanghai during tumultuous 1920’s in China. In his last few days (he died in 1986) he spoke to me about alchemy – in fact it was his overwhelming concern that I should work on making the idea of alchemical practice available to the West. And I knew nothing about it! So I dived into what was in translation at that time. There was actually very little. The oldest work, written in the 2nd century AD was this text – which I have presented as The Secret of Everlasting Life. It is primarily a Qigong manual, in fact the very first to be written, anywhere in the world! So I cut my teeth on this and its Chinese commentaries. All my work is based upon my reading of the Chinese commentaries – and on how they were explained to me by Giafu. In this I think I was blessed, in having the ‘key’, as it were – his oral instruction – to unlock this extremely intricate puzzle.

The Secret of Everlasting Life. It is primarily a Qigong manual, in fact the very first to be written, anywhere in the world! So I cut my teeth on this and its Chinese commentaries. All my work is based upon my reading of the Chinese commentaries – and on how they were explained to me by Giafu. In this I think I was blessed, in having the ‘key’, as it were – his oral instruction – to unlock this extremely intricate puzzle.

What do you mean, then, by this ‘intricate puzzle’?

Actually this puzzle is just the Chinese Mind! I feel strongly that the Chinese ideas and skills, knowledge and techniques (including acupuncture) should be taken within their own context – you cannot just import techniques and not understand the background teaching and philosophy. It really will not work.

You are referring to acupuncture perhaps? Where more ‘medical’ acupuncturists, such as doctors and nurses use acupuncture without a full apprenticeship?

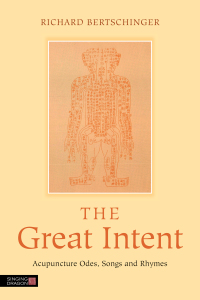

Not really, I think that acupuncture can survive any usage. It is resilient enough! But certainly without the dedication of a three year training you are not going to be using its full potential. And you are not giving patients the best either! Anyway, this leads on to The Great Intent, which is actually a re-working of The Golden Needle, a book published earlier in 1991. Singing Dragon was quite keen to reprint this, so I expanded and rewrote the introduction. This is a first translation of many of the odes, song and poems which have, for centuries, been used in teaching acupuncture theory and technique. Again I was keen to get all these ideas out to medical practitioners, who wanted to begin exploring some of the greater subtleties of needling – as well as brush up their theoretical knowledge. I know these poems have proved an inspiration to many.

Not really, I think that acupuncture can survive any usage. It is resilient enough! But certainly without the dedication of a three year training you are not going to be using its full potential. And you are not giving patients the best either! Anyway, this leads on to The Great Intent, which is actually a re-working of The Golden Needle, a book published earlier in 1991. Singing Dragon was quite keen to reprint this, so I expanded and rewrote the introduction. This is a first translation of many of the odes, song and poems which have, for centuries, been used in teaching acupuncture theory and technique. Again I was keen to get all these ideas out to medical practitioners, who wanted to begin exploring some of the greater subtleties of needling – as well as brush up their theoretical knowledge. I know these poems have proved an inspiration to many.

Now tell us a little about Yijing: Shamanic Oracle of China. I understand the Yijing has been referred to as ‘the oldest book in the world’. How can you justify such a statement!

Because the Yijing has its origins, and no one would deny this, in the oracle bones, the scapula of oxen, tortoise shells and the like, which have been unearthed recently in China. These prove that an oracle much like the Yijing (or ‘Book of Change’) was in use some 3000 years ago, in Bronze Age China. The Yijing is all about communicating with the unseen and unsaid. It is an oracle, yes, but also has a philosophy around it of Yin and Yang, the flux within the universe, light and dark, day and night, winter and summer, and the life and death of all living things. It is thus at the threshold of putting an understanding of these things into words – it uses images to communicate ideas, on the borderline of thought, as it were. And this was all happening 3000 years ago, before there were any books! So unlike the Dead Sea Scrolls or Egyptian Scriptures, the Yijing was trying to be useful – not trying to hand down a received wisdom, or deal of concepts. It was about meaning. About the meaning of life, about greatness – about what it is to be human! Like so much of Chinese philosophy, it told us how to live.

Because the Yijing has its origins, and no one would deny this, in the oracle bones, the scapula of oxen, tortoise shells and the like, which have been unearthed recently in China. These prove that an oracle much like the Yijing (or ‘Book of Change’) was in use some 3000 years ago, in Bronze Age China. The Yijing is all about communicating with the unseen and unsaid. It is an oracle, yes, but also has a philosophy around it of Yin and Yang, the flux within the universe, light and dark, day and night, winter and summer, and the life and death of all living things. It is thus at the threshold of putting an understanding of these things into words – it uses images to communicate ideas, on the borderline of thought, as it were. And this was all happening 3000 years ago, before there were any books! So unlike the Dead Sea Scrolls or Egyptian Scriptures, the Yijing was trying to be useful – not trying to hand down a received wisdom, or deal of concepts. It was about meaning. About the meaning of life, about greatness – about what it is to be human! Like so much of Chinese philosophy, it told us how to live.

Well, that is quite a topic. The last two books you mentioned about are Everyday Qigong Practice…

Well, that is quite a topic. The last two books you mentioned about are Everyday Qigong Practice…

That one ‘does what it says on the tin’. It is a simple introduction to Qigong exercises, with brilliant diagrams by Harriet Lewars – you can pick it up, and seconds later be practicing qigong, and circulating the Qi.

And the last, Essential Texts in Chinese Medicine: The Single Idea in the Mind of the Yellow Emperor?

This is my latest book. It is a digest of the medical writings contained in the Huangdi Neijing, or Yellow Emperor’s Book of Medicine, the great compendium of medical studies produced during the Han, and which has provided the backbone of all traditional medicine in the East for the last two-thousand years. I was fortunate, again, to pick up a copy of a condensed version of this book in 1981 at Stillpoint, Colorado, where I was studying with Giafu Feng – and he started me off with some tape recordings, he would get up 4 am, make a large pot of Earl Grey tea, which we would share and off he would go, extemporising a translation ‘on the hoof’ as it were of this book. Page One, Chapter One. It took him perhaps three months to finish, and I had to leave before it was done, but the next spring I remember him arriving at Heathrow airport with a large carrier bag in his hand, ‘here you are Richard the Book of Medicine, finished!’ There was no way I could turn down a commission such as this! So I have been working at producing a readable version of this text. Firstly I translated the Chinese commentaries, most from the Ming and Qing, then I collated them with his version. Then I also interleaved my own acupuncture studies and notes from Jack Worsley’s teachings and finally, after many years work, I have a version which I think is just about ready to go to press. It grew in the making, but from quite early on I saw that there was one thread running through the whole – this is obvious to anyone who begins to read the book. This one thread I rather grandly name ‘the single idea’ – really it describes the workings of Yin and Yang and the Five Elements. Once you can get a handle of what they are talking about and how they work, you really do have Chinese medicine ‘in your pocket’, as it were.

This is my latest book. It is a digest of the medical writings contained in the Huangdi Neijing, or Yellow Emperor’s Book of Medicine, the great compendium of medical studies produced during the Han, and which has provided the backbone of all traditional medicine in the East for the last two-thousand years. I was fortunate, again, to pick up a copy of a condensed version of this book in 1981 at Stillpoint, Colorado, where I was studying with Giafu Feng – and he started me off with some tape recordings, he would get up 4 am, make a large pot of Earl Grey tea, which we would share and off he would go, extemporising a translation ‘on the hoof’ as it were of this book. Page One, Chapter One. It took him perhaps three months to finish, and I had to leave before it was done, but the next spring I remember him arriving at Heathrow airport with a large carrier bag in his hand, ‘here you are Richard the Book of Medicine, finished!’ There was no way I could turn down a commission such as this! So I have been working at producing a readable version of this text. Firstly I translated the Chinese commentaries, most from the Ming and Qing, then I collated them with his version. Then I also interleaved my own acupuncture studies and notes from Jack Worsley’s teachings and finally, after many years work, I have a version which I think is just about ready to go to press. It grew in the making, but from quite early on I saw that there was one thread running through the whole – this is obvious to anyone who begins to read the book. This one thread I rather grandly name ‘the single idea’ – really it describes the workings of Yin and Yang and the Five Elements. Once you can get a handle of what they are talking about and how they work, you really do have Chinese medicine ‘in your pocket’, as it were.

Singing Dragon received the Gold prize in the Enlightenment/Spirituality category for

Singing Dragon received the Gold prize in the Enlightenment/Spirituality category for