Betty Sutherland is the founder and director of UK Tai Chi and ‘Chi for Children’, a leading provider of Tai Chi based initiatives in schools across the UK. She has studied Tai Chi Chuan since 1994 and is a senior instructor at the Five Winds School of Tai Chi Chuan. She is also a member and listed as an ‘A’ grade instructor with the Tai Chi Union for Great Britain and a member of the British Council for Chinese Martial Arts.

Betty Sutherland is the founder and director of UK Tai Chi and ‘Chi for Children’, a leading provider of Tai Chi based initiatives in schools across the UK. She has studied Tai Chi Chuan since 1994 and is a senior instructor at the Five Winds School of Tai Chi Chuan. She is also a member and listed as an ‘A’ grade instructor with the Tai Chi Union for Great Britain and a member of the British Council for Chinese Martial Arts.

Here, she answers some questions about her new book and DVD, Chi for Children: A Practical Guide to Teaching Tai Chi and Qigong in Schools and the Community.

How did you get in to Tai Chi Chuan, and what do you love about it?

I was originally directed to Tai Chi to help me during a very stressful time in my life. I was actually being ‘bullied’ in work by a boss and this was taking a serious toll on my health and mental wellbeing. A neighbour saw me with a dreadful migraine (I was having regular debilitating migraines) and she said “Take up Tai Chi – you need grounding”. She said this regularly for 2 years until I did indeed ‘take up Tai Chi’. It helped me work out my situation and deal with the daily mental punishment in the work situation, and other people began to notice that I was dealing with things a lot better. I will always thank my neighbour for her insight. (Incidentally years later the ‘boss’ took up Tai Chi!)

To this day Tai Chi is still my solitude and when things go wrong, my head says “Do Tai Chi” and I am compelled to go and do some form – it’s weird but it works.

What was the impetus for establishing UK Tai Chi? How have you found running Tai Chi and Qigong classes in schools?

I was asked to go into a school for their International Day and do a little bit on China. When the teachers saw how calm the students became while doing Tai Chi, they asked me to do more and show them how to help their students by teaching them Tai Chi. Hence the programme of Educational Tai Chi and Qigong called ‘Chi for Children’ was born, and train-the-trainer (the foundation for this resource) established in schools. In 2002 my programme was supported by school sports management and rolled out across Yorkshire (and now beyond).

Most teachers have embraced Tai Chi and the Chinese approach to life, so much so, that I now have several teachers in my traditional Wudang Tai Chi Chuan evening classes. On the whole the educational ‘establishment’ see the benefits to students, especially for the calmness that Tai Chi brings to the classroom. They also recognise the benefits of teaching students how to ‘manage the mind’ and improve their ability to focus and in the long term improve discipline. Mostly students (mainly 6-11 years old) love it and as they calm their energies and come alive to the movements they report mainly good feelings about themselves, of feeling calm but happy and often pleasantly surprised that they can feel Chi (energy) in their bodies. Often teachers attending these sessions will comment on how calm the class becomes during and after Tai Chi.

I have lots of letters and drawings from kids who have enjoyed the Tai Chi sessions, but the one I remember most was a little girl who had obvious learning difficulties. At the end of the session she came up to me and said “Miss, I didn’t think I would be able to do this, but I can”, with a big beaming smile on her face. This to me was the best reward that I could have asked for.

I also have a teenager who was withdrawn and a loner because of family difficulties. This student has since competed in Tai Chi at local and national level. However to me the best thing that has happened to him is that he has stepped forward to mentor and nurture some of the younger pupils and was recently pictured with his arms round them laughing and smiling. Like myself these students have embraced Tai Chi and are reaping the benefits.

How did the book and DVD come about, and what is the idea behind it?

In the early days teachers who wanted to sustain Tai Chi in schools asked me for a teaching resource; they stressed that it would be easier for them if it was in a visual format. I sat down and worked out how I was delivering the sessions and wrote it all down. This was the foundation of the DVD and book. It is for anyone who wants to learn the basics to teach to the younger age group.

How does Tai Chi support children’s physical, mental, emotional and academic development?

In Traditional Chinese Medicine the emotions and physical health work hand-in-hand, one balancing the other. When we follow these principles and teach them to the younger generation they benefit from an early age. Recognising that stress, fear and adrenalin inhibits learning, we teach students how to manage the mind, reduce negative emotions and improve and enhance a positive attitude. This in turn can benefit their emotional and academic development, and also helps going forward in life (interviews, driving exams etc.).

On a physical level, I have found that children are not as fit as they could be for their age. Tai Chi is not ‘an easy option’ – it just looks easy. Tai Chi is a ‘weight bearing’ exercise and holding postures develops muscles and bone density. In Tai Chi we ensure that don’t over-stretch or ‘hyper extend’ in the way that some other exercise systems can. A session last between 45 – 60 minutes and the students are standing for that period of time. Most comment that ‘it’s hard work’.

What advice would you give to someone looking to introduce Tai Chi into school and community settings?

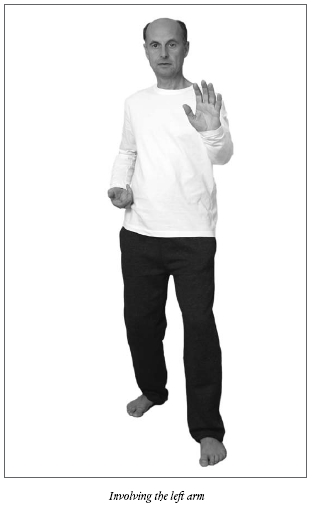

I would recommend that teachers attend a Tai Chi class, however my resource Chi for Children will lead the teacher through the basic forms and postures that they need to help them get started. Each and every action is shown in the easy to follow DVD and explained in the book – a teacher could start to teach some of the simpler posture from day one. I know this because I have taught several hundred teachers/activity and community leaders backed by my resource.

Tai Chi is an excellent way to start the day and calm the classroom environment. I would recommend that teachers take learning slowly and as I say in the book – “Encourage your students to help you as you are also ‘new to the subject’. Empowering others always gets lots of enthusiasm.”

Praise for ‘Chi for Children’ from the Barlby Sports Partnership:

“The ‘Chi for Children’ program, delivered by UK Tai Chi has made a huge impact within the Barlby School Sport Partnership.

After a comprehensive review of the partnerships activities, it became apparent that, young people wanted more from their current physical education program. There was also a real need to target those children that took little or no interest in the traditional team activities that were currently being offered.

Alongside this the School Sport Partnership wanted to run an initiative that not only captured the imagination of all the young people involved but offered primary teaching staff the opportunity to gain a qualification in delivery archived through a excellent personalised mentoring scheme offered by UK Tai Chi.

The impact to date has been huge, 20 primary schools (45% of all schools) have been involved with the Chi for Children initiative, with over 20 teachers attending the train the trainer module 1. Over 200 pupils now regularly participate in Tai Chi either in the classroom as a focus session or as a stand alone PE lesson. One school was even used as a show piece example in the Partnership Dance Platform event.

As well as the health and physical benefits to all the young people what has been most encouraging is the impact the initiative has had within the whole school. Schools have been using Tai Chi as a means of stress relief for pupils (and staff) prior to exams, as a means of calming children down after lunchtimes, as a way of focusing children in the mornings to start the day.”

Copyright © Singing Dragon 2011.

Singing Dragon received the Gold prize in the Enlightenment/Spirituality category for

Singing Dragon received the Gold prize in the Enlightenment/Spirituality category for  In this interview, Singing Dragon author

In this interview, Singing Dragon author

James Drewe

James Drewe

Master Wu has devoted himself to the study of Qigong, martial arts, Chinese medicine, Yijing science, Chinese calligraphy, and ancient chinese music for over 30 years. He was Director of the Shaanxi Province Association for Somatic Science and the Shaanxi Association for the Research of Daoist Nourishing Life Practices, and has written five books and numerous articles on the philosophical and historical foundations of China’s ancient life sciences. Visit

Master Wu has devoted himself to the study of Qigong, martial arts, Chinese medicine, Yijing science, Chinese calligraphy, and ancient chinese music for over 30 years. He was Director of the Shaanxi Province Association for Somatic Science and the Shaanxi Association for the Research of Daoist Nourishing Life Practices, and has written five books and numerous articles on the philosophical and historical foundations of China’s ancient life sciences. Visit  Your book is the result of a research study funded by the NHS. What motivated you to launch this study of Qigong and MS, and to write the book?

Your book is the result of a research study funded by the NHS. What motivated you to launch this study of Qigong and MS, and to write the book?