Richard Bertschinger studied for ten years with the Taoist sage and Master, Gia-fu Feng. A practising acupuncturist, teacher of the healing arts, and translator of ancient Chinese texts, he works and practises in Somerset, England. Here, he explores some key concepts of Qigong, showing just how universally beneficial the practice is, and how easy it is to pick up.

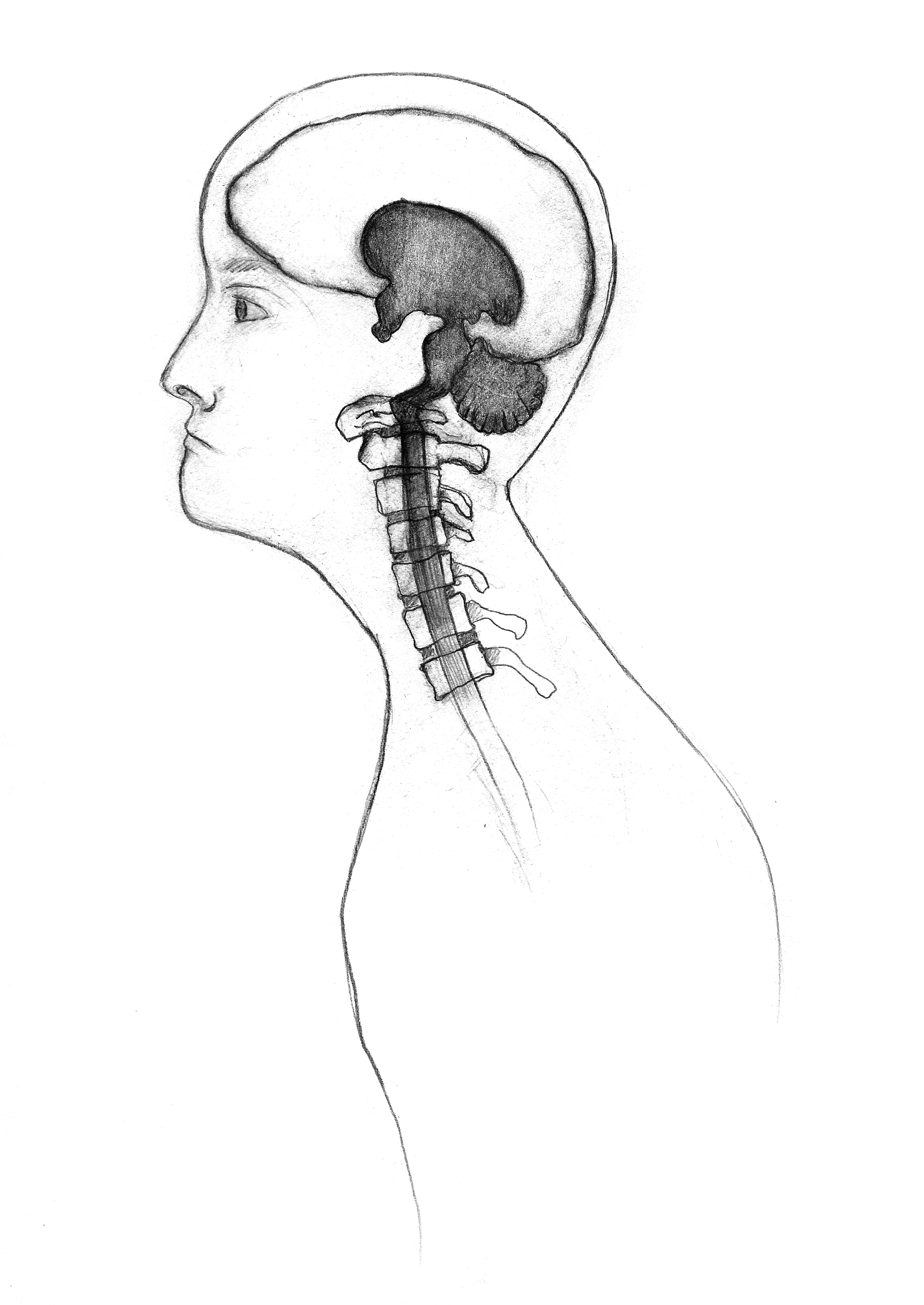

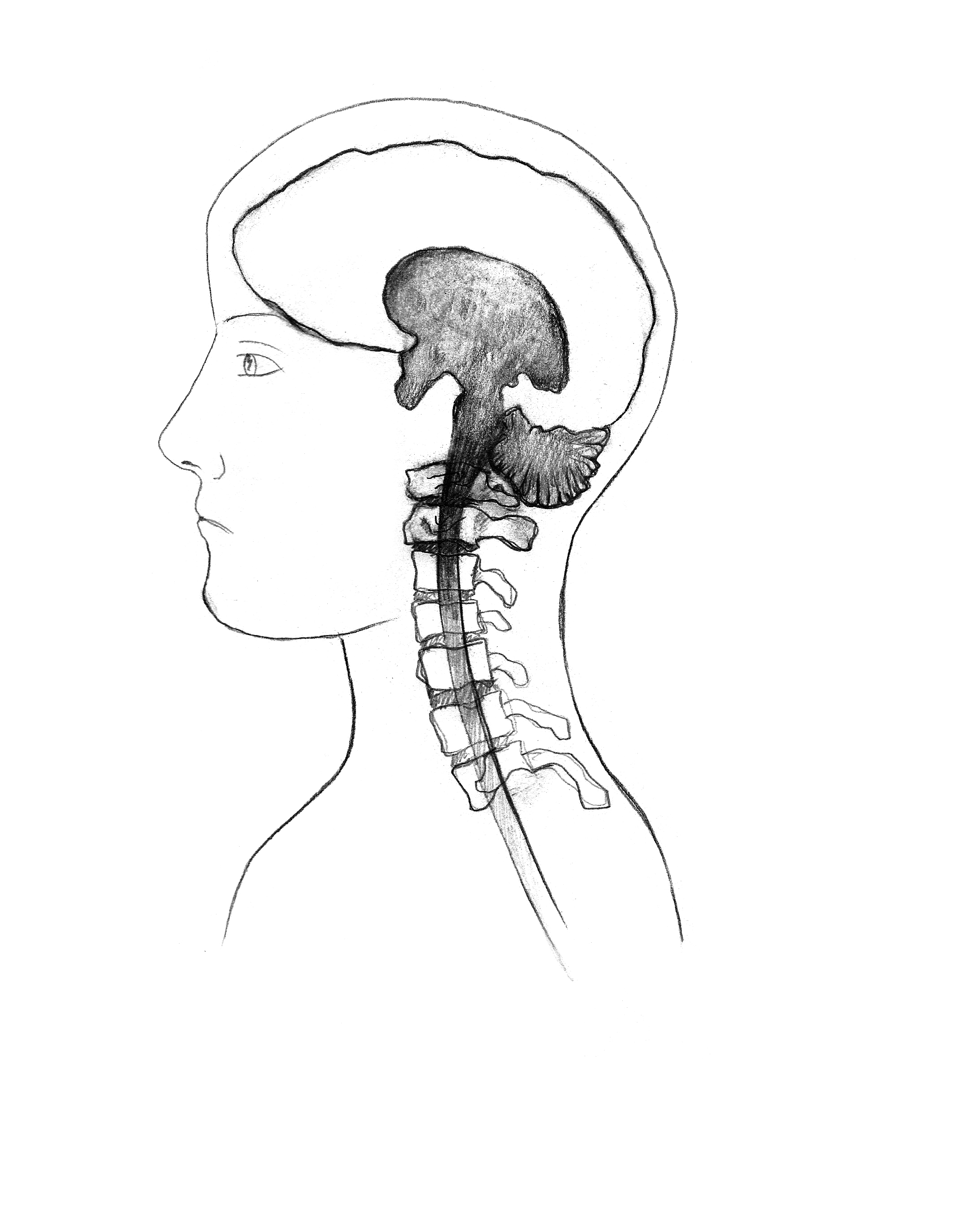

* Qigong can also be called Dao Yin which means guiding or leading the Qi. So many problems come from blockages inside the tissue, so the idea is that you keep moving the Qi to loosen these blockages. There’s a wonderful saying ‘Door hinges never rot and running water never goes stale’, which brings out movement as primary to health. When you read about the biology of modern science you see that this concept is also biologically important: it’s the circulation of fluids and gases in the cell that provides the conditions for life. The interchange at the boundary of the cell is so important for the release of oxygen, the oxygenation of the tissue, the internal respiration of the cell. Here, it’s movement which is conducive to life.

* Originally these exercises were taught master to pupil and from father to son. You learnt, as one might say, energetically, through your skin, just by watching and following behaviour, on a very deep level. Now, when teaching we have to approach this learning slightly differently because you might get a group of 20 new people in a class that you might never see again. The starting point is to move the body. If students move their bodies the energy and breath will follow eventually, and they will get the secret. The brain itself will begin to adjust of its own accord. And the mind follows.

* Everyone has a different path. No-one comes in and qualifies 3 years later. One of the main principles behind Chinese medicine is that you suit the treatment to the individual and the condition – which of course can change. So with these exercises we’re looking for appropriateness. People can take from the book what they need at the time. What is wonderful is that it is such a natural practice and can adapt to many conditions. There is not one orthodox way, so long as you are following natural forms.

* It’s important to have one particular space where you do these exercises and one particular time of day to do them. It’s difficult to just slip them in anywhere. However, I’m a great believer in us all being gifted amateurs. I think that people can very much take this practice home and do it themselves. I’ve seen students do most interesting things with exercises that I have taught them – you pick it up and pass it on.

* In Ezra Pound’s translation of the Confucian classic Da Xue, he highlights the saying ‘as the sun makes it anew, day by day make it new, every day make it anew’. My teacher Gia Fu Feng would encourage us to ‘rediscover’ the Qi everyday. We have to do this everyday or it gets covered over by the troubles, worries and issues of the world. I think it attests to the genius of the Chinese that they found a way to winkle out that health from our lives and to keep it there at a good level, keeping a good balance

* To have something that you can do under your own hands is just so valuable. Drugs are important but you don’t have to go down that route all the time – a lot is in our own hands. I’ve seen people come in with painful stomachs or painful knees, and if they do the rubbing exercises they improve. People with long-term conditions often respond well to Qigong as you are dealing with the smaller, finer (neuro-humeral) mechanisms in the body. When you practice in a gentle, conducive manner you actually have minute little chemical changes, which can make a great difference to overall wellbeing.

© 2012 Singing Dragon blog. All Rights Reserved.