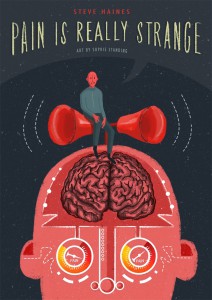

In this article, Steve Haines shares his thoughts on memory and trauma, and how important it is to recall past memories. Steve Haines is the author of medical graphic book Pain is Really Strange. His new book Trauma is Really Strange will be available on the 21st December.

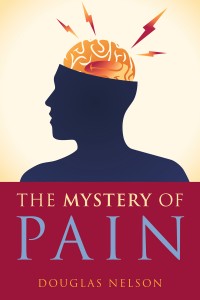

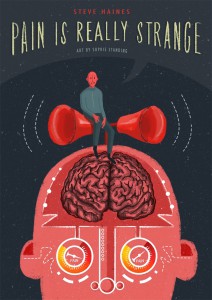

The old primitive brain is shown in blue and red: the limbic system, brain stem and cerebellum.

Some Thoughts On Memory

Where are memories stored? In order to heal trauma, how important is it to remember what happened? These are common questions that often come up working with clients and teaching on trauma.

There are folklore phrases such as ‘muscle memory’ and ‘cellular memory’ that can be very useful but need to be applied carefully. They speak to the importance of information stored in the body. However it is essential to understand that for the information to be available to our awareness, our brain needs to be involved in processing the patterns of information flow happening in the body. Where the information is processed – in the primitive brain (unconscious) or in the cortex (conscious) – determines whether or not the memory is explicit.

I have a favourite old pair of jeans right now, some holes are on the second round of stitching. The wrinkles and folds in the material are a memory of sorts, the jeans mould to my body like no other pair of trousers. The fascia researcher Gil Hedley (2005) talks about fascia as ‘fuzz’. The fuzz accumulates and represents time. A certain stickiness and alignment of the fibres in the tissues holds the joints in more habitual ways.

Imagine a small child being shouted out by her father. Her shoulders tense, her neck tightens and there is a surge of fear related hormones and activity in the body. If this happens continuously the pattern of ‘shoulders tense and neck tight’ becomes a deep ‘action pattern’ (Kozlowska et al 2015).

Now imagine 30 years later the adult is on your treatment table. With grounded presence and soft, safe, warm, hands you are holding her head and neck. The tissues in her neck begin to express long held contractions and tightness. A shape in her body emerges, similar to the pattern generated when she got shouted at. Your client begins to feel unease and may think about her father.

The ‘muscle memory’ is the tension and tone in the tensegrity of the neck (Ingber 2008). The ‘cellular memory’ is cellular membrane receptors on local and global cells that grew to be sensitive to the all the stress hormones, immune system signaling and inflammatory chemicals that used to be secreted in the fear response (Damasio and Carvalho 2013). The ‘action patterns’ are simple, default movement schemas held in the old primitive brain.

Sensory nerves signal the changes in tension and chemical milieu to the brain. Only with the brain involved do we have emotions, feelings and thoughts generated in awareness. They may or may not be fully integrated into cognition, but something is happening. A memory is being expressed.

Instead of explicit memories we can have implicit memories (I first heard this term from Babette Rothschild, 2000), here the activation is chiefly in the primitive brain (brain stem, cerebellum and limbic system). The client on the table becomes scared when you touch her neck and too much changes too soon, but she does not really know why she is getting upset.

As a therapist working with trauma it is important to note the surges and changes in the rhythmic activity of the body as implicit memories occur. There are some great early warning signals that something is happening.

We can then help find the right pace of change for the individual so they can learn to self-regulate. The therapist’s skillful presence can lead to co-regulation such that the individual can learn to self-regulate (Ndefo 2015). The primitive brain does not do words and concepts very well, but will respond to safety, touch and presence.

Implicit memories are coded very simply in the primitive brain. Often they are without a timeline. The amygdala – an important part of our threat detection system (LeDoux 2015) – holds lots of symbolic representations of threat. The amygdala will trigger ‘fight-or-flight’ or ‘immobility’ responses (‘defense cascade’ Kozlowska et al 2015) if it senses danger in the incoming information stream.

If the cortex gets involved then we will have explicit memory – we can pull in associated events and a timeline to contextualise the activity in the body. Explicit memories usually only emerge into awareness after the body has changed. The hippocampus and prefrontal cortex should help us say ‘That happened 30 years ago’. The skill of the therapist here is to honor the memories and stories that appear but keep orienting the client to resources in the body and environment; ‘Its not happening now’, even if your body is screaming at you be scared.

Following Dr David Berceli (2008), founder of Trauma Releasing Exercises (TRE), I am fond of saying ‘You do not need to remember or do not need to understand to heal trauma’. The goal is to overwrite the symbols in the amygdala with present time information. The body is a great source of good news that can bring you into now.

Summary

Information is stored in the tissues and cells of the body.

The threat detection systems in the primitive brain can be activated as the body changes.

The primitive brain does not do words and concepts very well, but will respond to safety, touch and presence.

If we can support change in the body and down regulate arousal we can change memories with out needing to understand or remember the trauma event.

The goal is to uncouple the charge of the defense cascade from the sensations of the implicit memory.

Notes

1 Kozlowska et al (2015) list some early signs of arousal. For flight-or-fight (their preferred order of this phrase) they list; changes in breath, furrowing of the eyebrows, the tensing of the jaw, or the clenching of a fist, narrowing of the range of attention. For immobility states they list; visual blurring, sweating, nausea, warmth, light-headedness, and fatigue.

My favourite signs to look out for are anything going too quick (thoughts, sensations or emotions that cannot be integrated into the present moment) and anything going too slow (spacey, floaty, absence, hard to make eye contact, numbness or tingling or loss of body awareness).

Dry mouth, sense of small or far away feet, absent belly, cold hands and a sense of someone withdrawing are all good signs to put the brakes on, whatever process is being expressed. David Berceli teaches ‘Freezing, Flooding or Dissociation’ as signs that too much arousal is occurring.

Download as pdf: memory v3 2015-10-29

References

Berceli D (2008) The Revolutionary Trauma Release Process. Transcend Your Toughest Times. Vancouver: Namaste Publishing.

Damasio A and Carvalho GB (2013) The nature of feelings: evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, Vol 14, February 2013, 143.

Hedley G (2005) The Integral Anatomy Series. 4 Vol DVD set. Integral Anatomy Productions, LLC, 430 Westwood Avenue, Westwood, NJ 07675, USA (or check ‘The Fuzz Speech’ on YouTube).

Ingber DE (2008) Tensegrity and mechanotransduction. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 12, 198–200.

Kozlowska K, Walker P, McLean L, and Carrive P (2015) Fear and the Defense Cascade: Clinical Implications and Management. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015 Jul; 23(4): 263–287.

LeDoux JE (2015) The Amygdala Is NOT the Brain’s Fear Center. psychologytoday.com http://bit.ly/ledoux-no-fear-center Accessed 2015-09-01

Ndefo N (2015) Personal communication. www.trelosangeles.com ‘Sometimes we have to co-regulate before we can self-regulate’.

Rothschild B (2000) The Body Remembers – The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment. London: W.W. Norton.

Medical graphic books by Steve Haines, published by Singing Dragon

Pain is Really Strange is a scientifically-based, detailed, and gently humorous graphic book on pain and pain management. Answering questions such as ‘how can I change my pain experience?’, ‘what is pain?’, and ‘how do nerves work?’, this short research-based graphic book reveals just how strange pain is and explains how understanding it is often the key to relieving its effects.

Trauma is Really Strange is a science-based medical graphic book explaining trauma, its effects on our psychology and physiology, and what to do about it. When something traumatic happens to us, we dissociate and our bodies shut down their normal processes. This unique comic explains the strange nature of trauma and how it confuses the brain and affects the body. With wonderful artwork, cat and mouse metaphors, essential scientific facts, and a healthy dose of wit, the narrator reveals how trauma resolution involves changing the body’s physiology and describes techniques that can achieve this, including Trauma Releasing Exercises that allow the body to shake away tension, safely releasing deep muscular patterns of stress and trauma.

Trauma is Really Strange will publish on December 21st 2015.