By Ioannis Solos

By Ioannis Solos

In pre-modern China, outbreaks of infectious/communicable diseases such as typhoid, plague, influenza, smallpox etc. were terribly common and dangerously contagious. Therefore, during such times, taking the pulse, speaking with the patient and even using acupuncture would often be a reckless way to interact with the sick.

For remedying this situation there was a great need for the development of a new approach in diagnosis, so physicians would be able to provide appropriate treatment while having minimal physical contact with the patient.

The first systematic Tongue Diagnosis system first appeared during the Jin and Yuan Dynasties, as an alternative to the Pulse method. It derived from the works of Scholar Ao (real name and period unknown) who was perhaps the first doctor to produce an ensemble of 12 tongue illustrations, in which appeared the common ailments of his era. Along with every image he also suggested a formula which – in his opinion – would be sufficient to appropriately manage each condition.

However, his manuscript, known as Little pieces of Gold (Shang Han Dian Dian Jin) was never meant to be public, and it appears that it has only been transmitted from teacher to selected disciples within closed circles, for centuries. This fact is also well described in Xue Li-zhai’s preface to the Scholar Ao’s Gold Mirror records, where it is said that:

‘Gentleman Ao set his own rules on the tongue diagnosis, and he thought that [they summarized] the essence for this special system. At the same time he wrote two books, the Little Pieces of Gold and the Gold Mirror Records, both [to be kept] as a secret and not be passed on. During [Emperor] Zheng De’s Wu-Chen year (1508) I met a person who was able to observe the tongue and prescribe [accordingly], and always with good clinical results. So I invited him to my home and tried to inquire about his method, but he refused to further elaborate about it.’

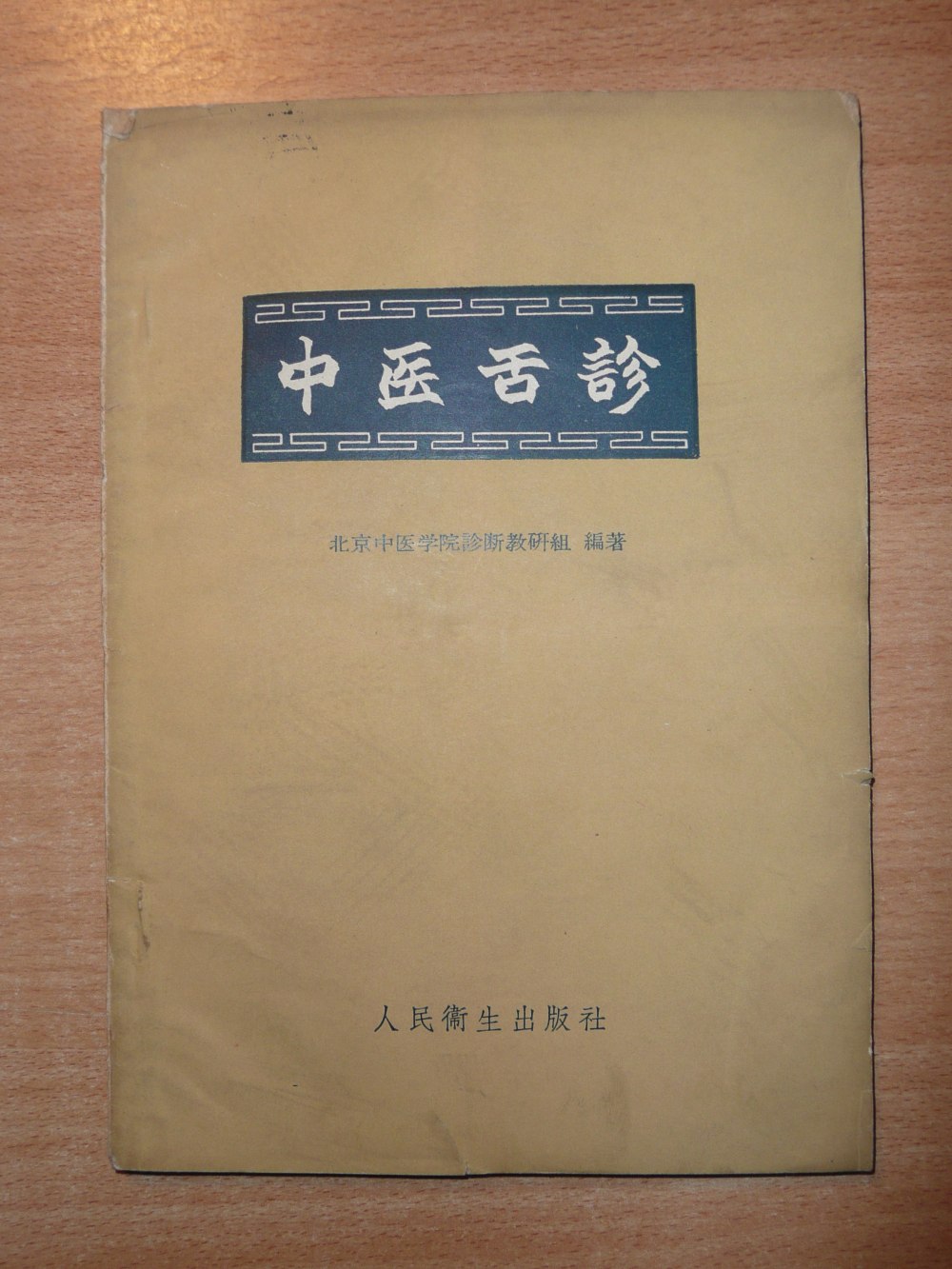

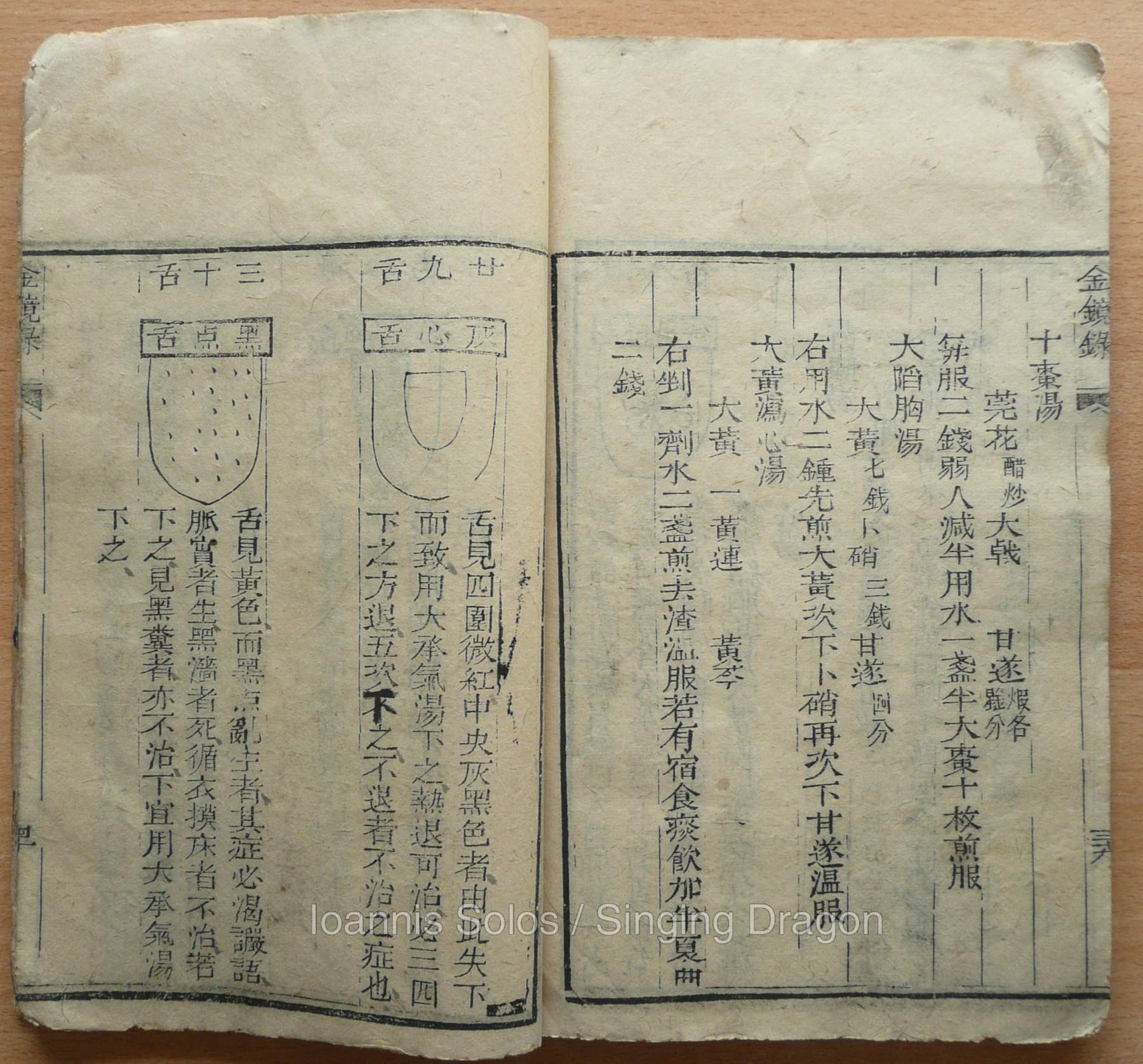

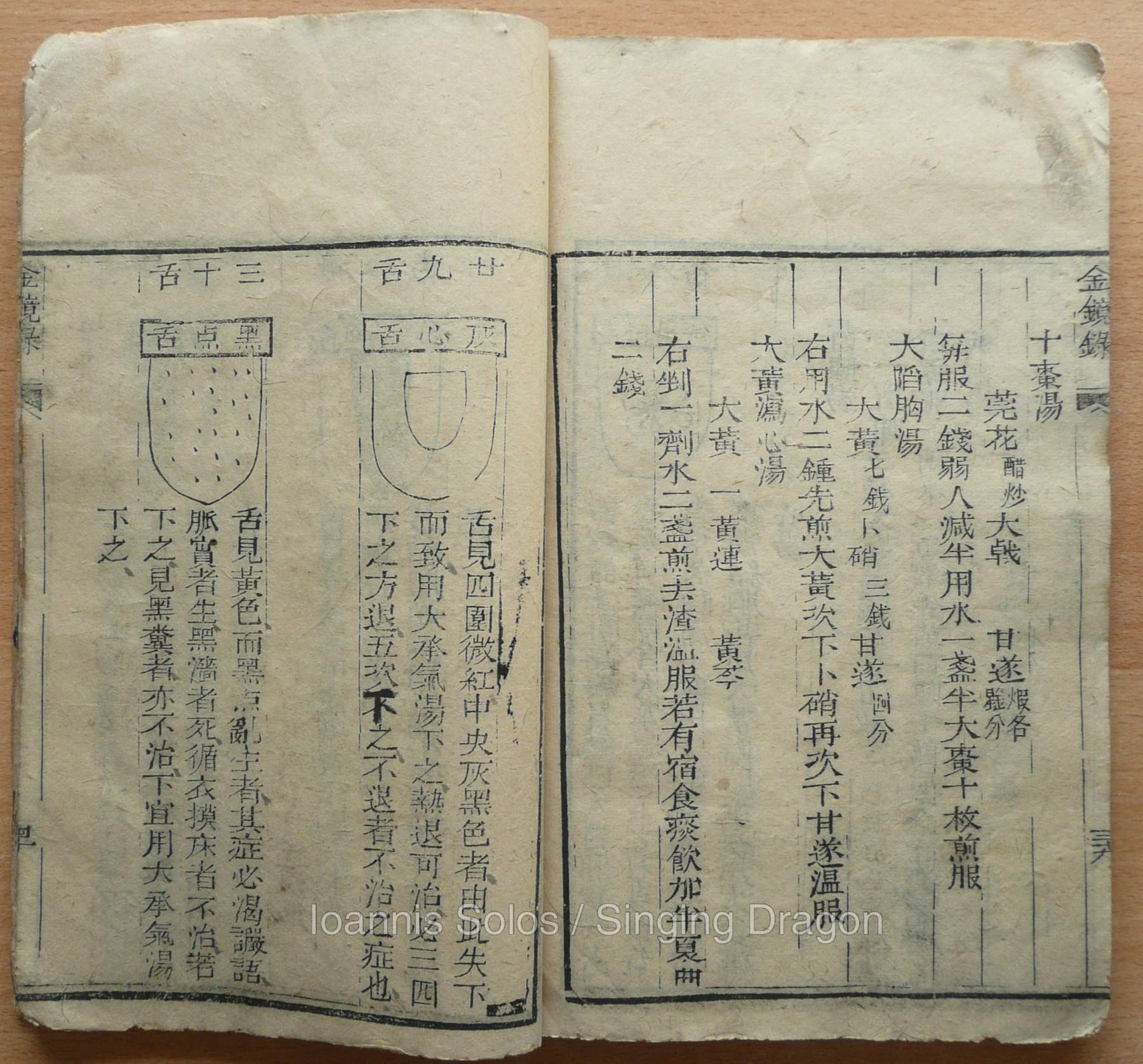

A page from the Imperial compilation of the “Scholar Ao’s Gold Mirror Records” Underneath each illustration there is a short explanation and a treatment approach including an herbal formula. Qing Dynasty circa 1850.

Historically, in 1341, a scholar from the Hanlin Imperial Academy named Du Qing-bi acquired a copy of Ao’s manuscript. He edited the original text and further contributed to it, with an additional 24 illustrations to a total of 36. He therefore presented a more complete overview of the various tongue reflections according to his own ideas. His book was eventually named Scholar Ao’s Gold Mirror records (Ao Shi Shang Han Jin Jing Lu) (Illustration 1). This book was very easy to use, but also extremely profound. It demanded that the doctors work out the essence of the tongue differentiation system by studying the 36 tongues and then further developing their own personal understanding via clinical practice and meticulous research.

Du Qing-bi in his original introduction summarizes this as follows:

‘The earliest twelve tongues [in Ao’s manuscript] unfortunately did not cover all the [possible] patterns [and therefore] I [personally] added twenty four illustrations and [the appropriate] treatment method on the left side, containing the formula. From each section, [you should] advance progressively, in order to determine the subtleties of life and death.’

However, in rural areas where there were no doctors, common people could also match the patient’s tongue to the appropriate illustration (much like in Ao’s original system), and prescribe medicine in the hope that the patient could be saved.

Ma Chong-ru records this in his endnote as follows:

‘Although some places may lack good doctors, however they should have some reference materials to assist the situation. For those who have no [such materials to provide some] cure; only the destiny may determine their life and death. [Therefore] the easiest path to treat the cold damage is by using cut-blocks for printing and to spread [the knowledge].’

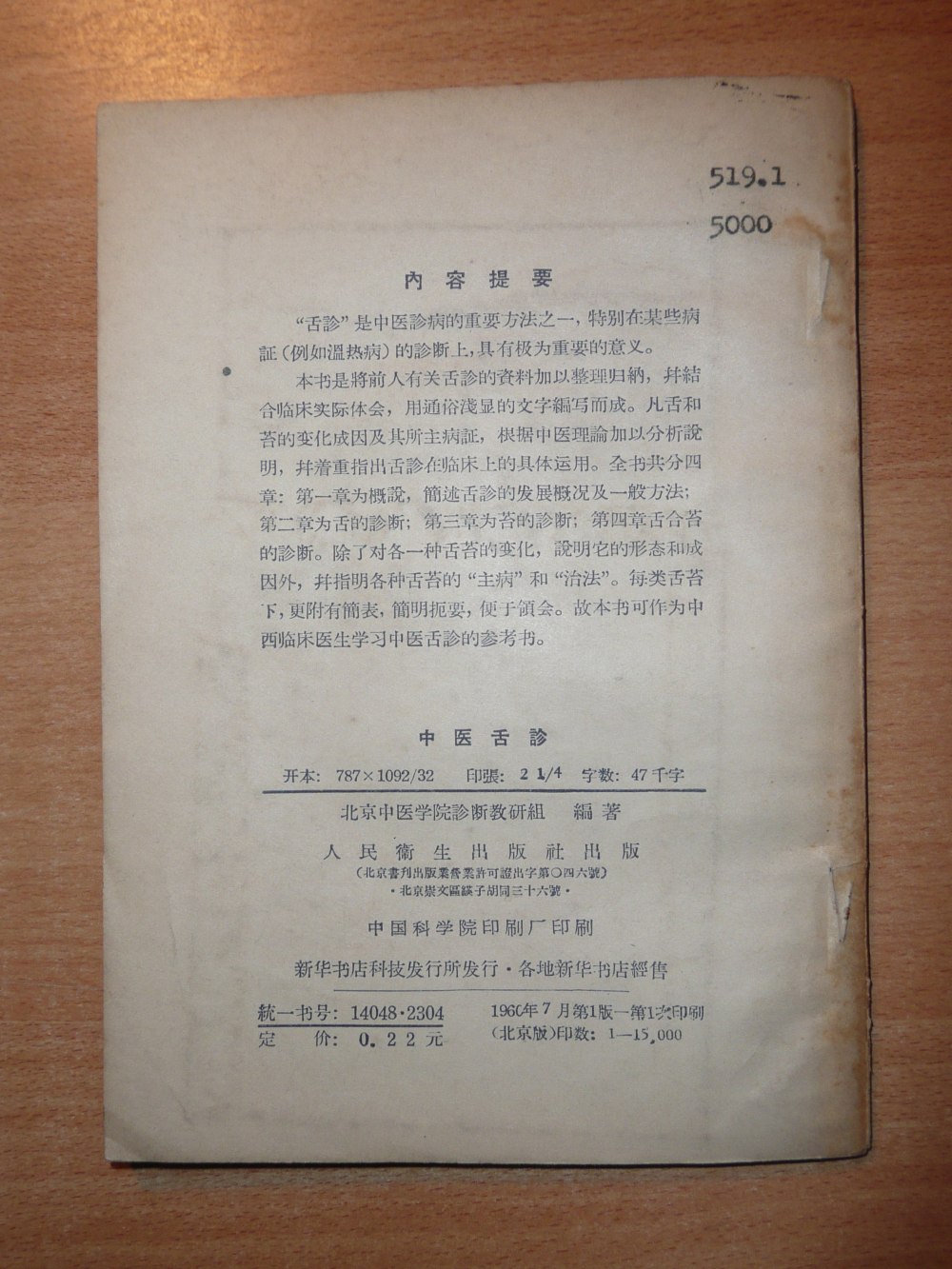

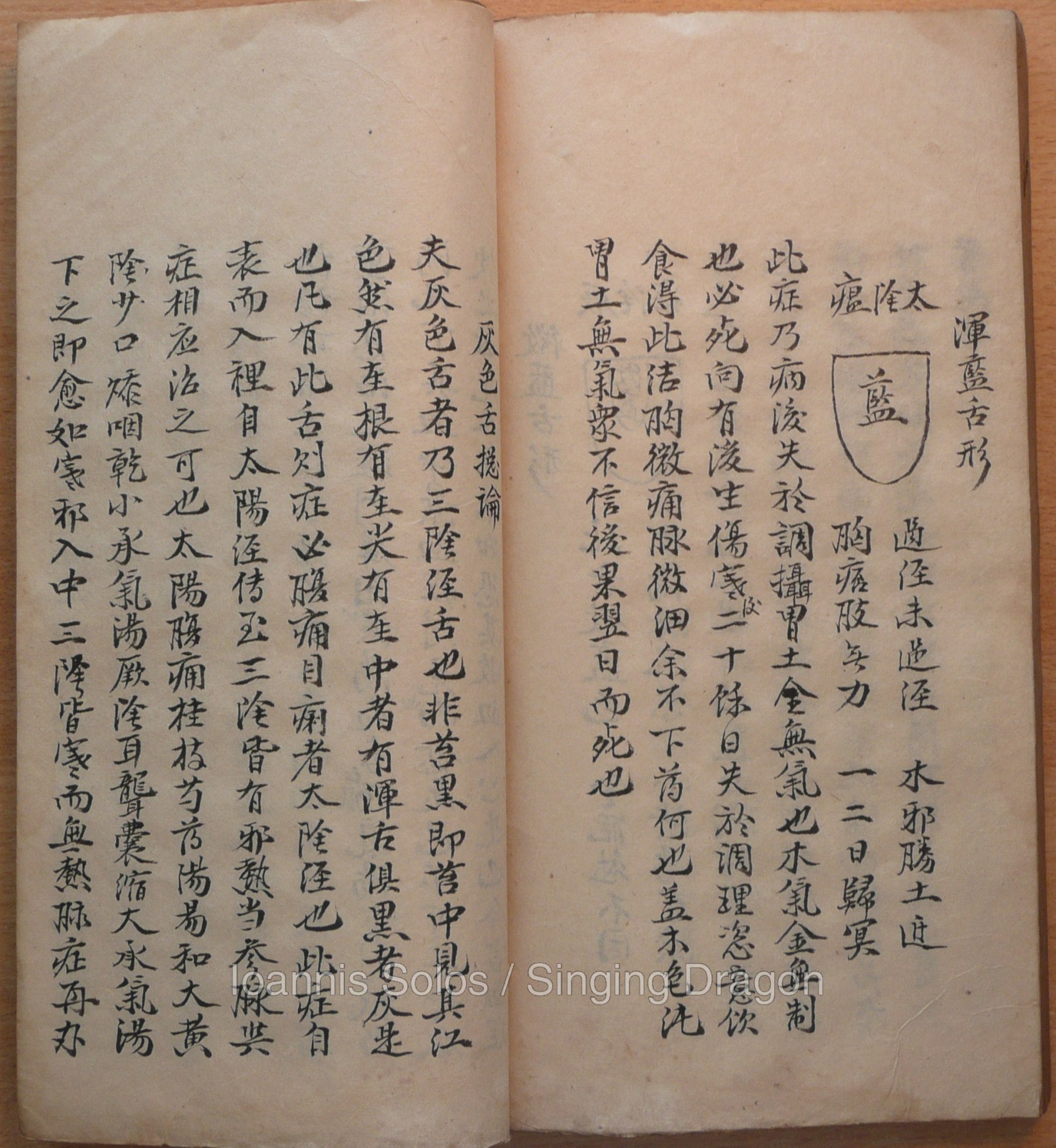

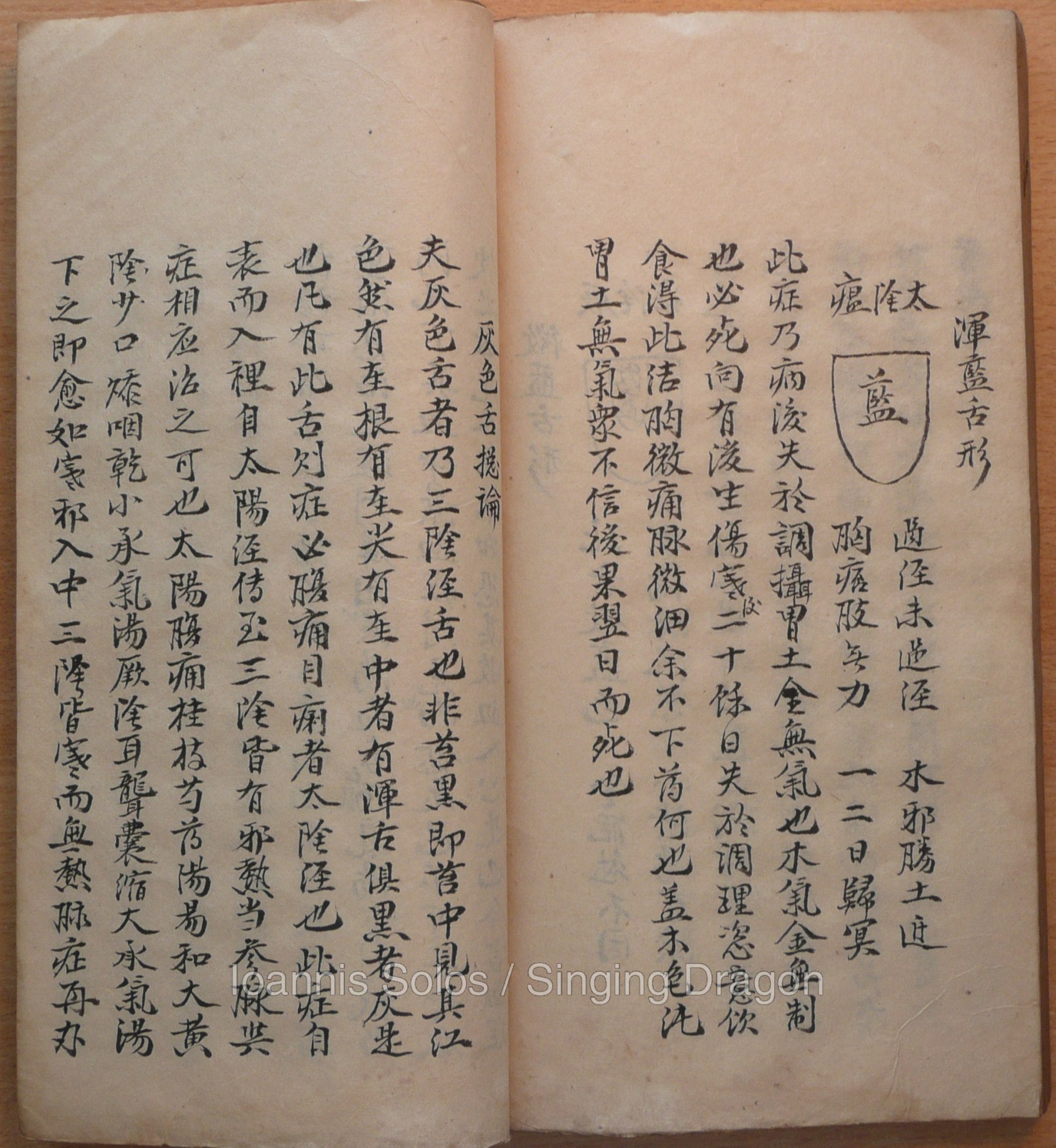

A tongue illustration from the “Essential Teachings on Tongue Observation in Cold Damage” and part of the summary on the grey tongue theory. Rare handwritten copy in the author’s possession, late Qing Dynasty, Guangxu era.

During the Ming Dynasty, and following the popularity of the Scholar Ao’s Gold Mirror Records, appeared the Essential Teachings on Tongue Observation in Cold Damage (Shang Han Guan She Xin Fa) (now lost in the print version). This book was a lot more detailed, and containing a total of 137 tongues. (Illustration 2) The Essential Teachings on Tongue Observation in Cold Damage provided each tongue with a lengthy explanation, formulae, and a poem to assist memorization. Although significantly more detailed than Ao’s manuscript, it never surpassed its predecessor in popularity. It appears that matching up the patient’s tongue to one of the 137 illustrations was a much harder task, and the lengthy explanations ultimately confused the doctors who wanted to fathom the author’s “root” methodology.

Eventually, during the Qing Dynasty, Zhang Deng edited/simplified the Essential Teachings on Tongue Observation in Cold Damage down to 120 tongues. Like he states in his introduction to The Tongue Reflection in Cold Damage:

‘[In this work] I corrected the mistakes appearing on the text of Guan She Xin Fa, dismissed all of its disordered inaccuracies, and thrown away the information that was not concerned with the cold damage. I have also added materials from my father’s case studies and notes on treatment, as well as materials from my own personal experiences. In total there are one hundred and twenty illustrations.’

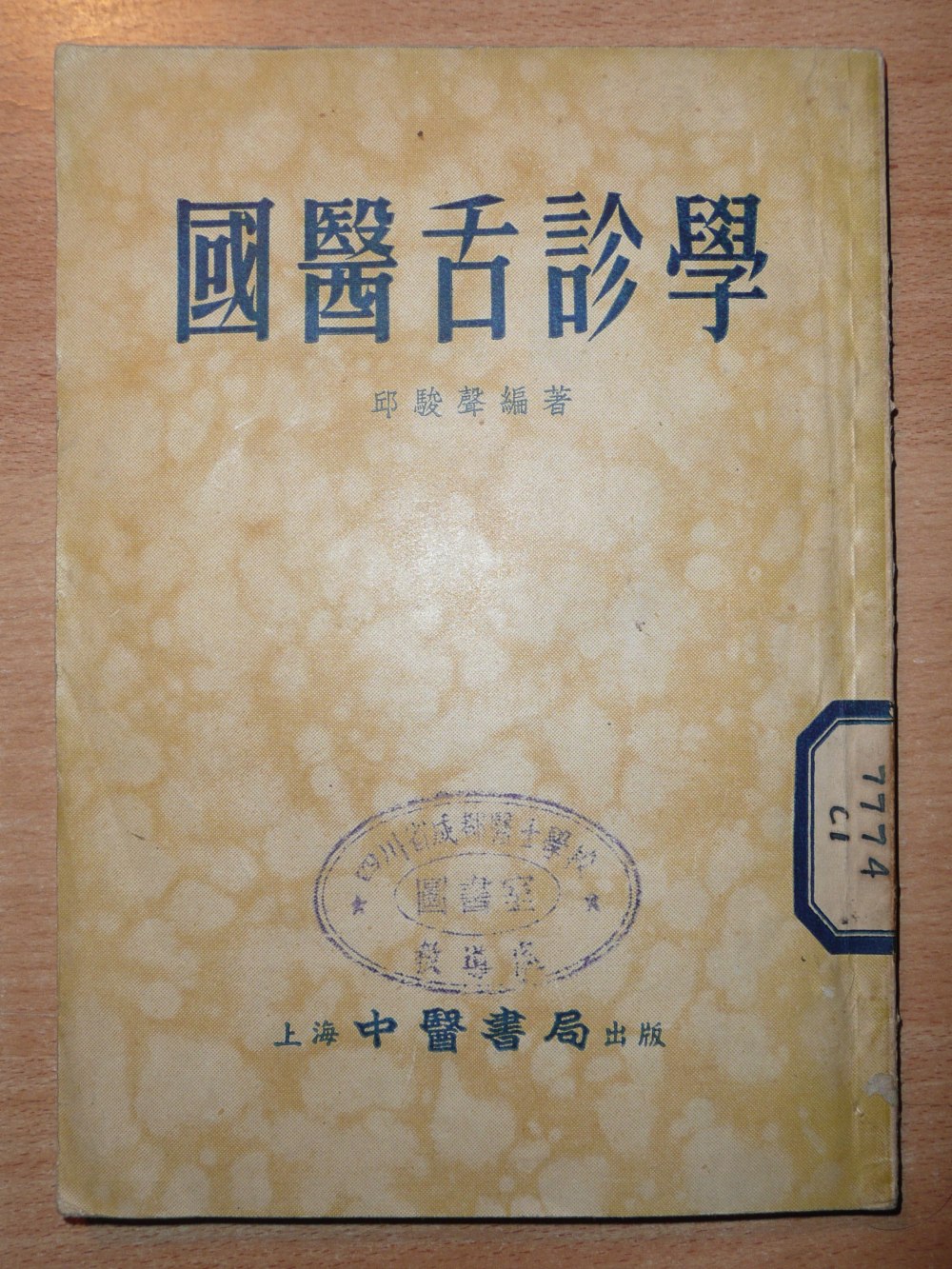

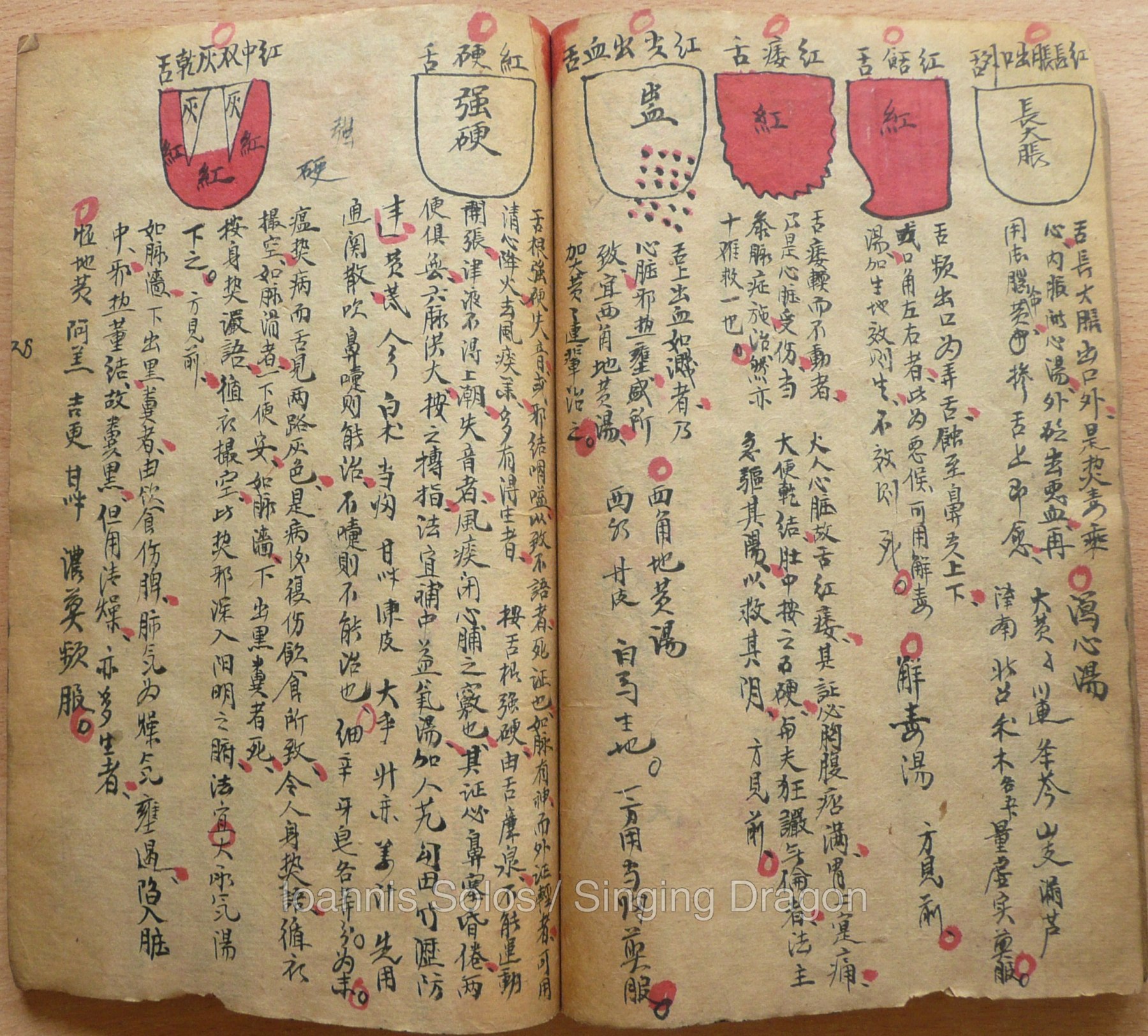

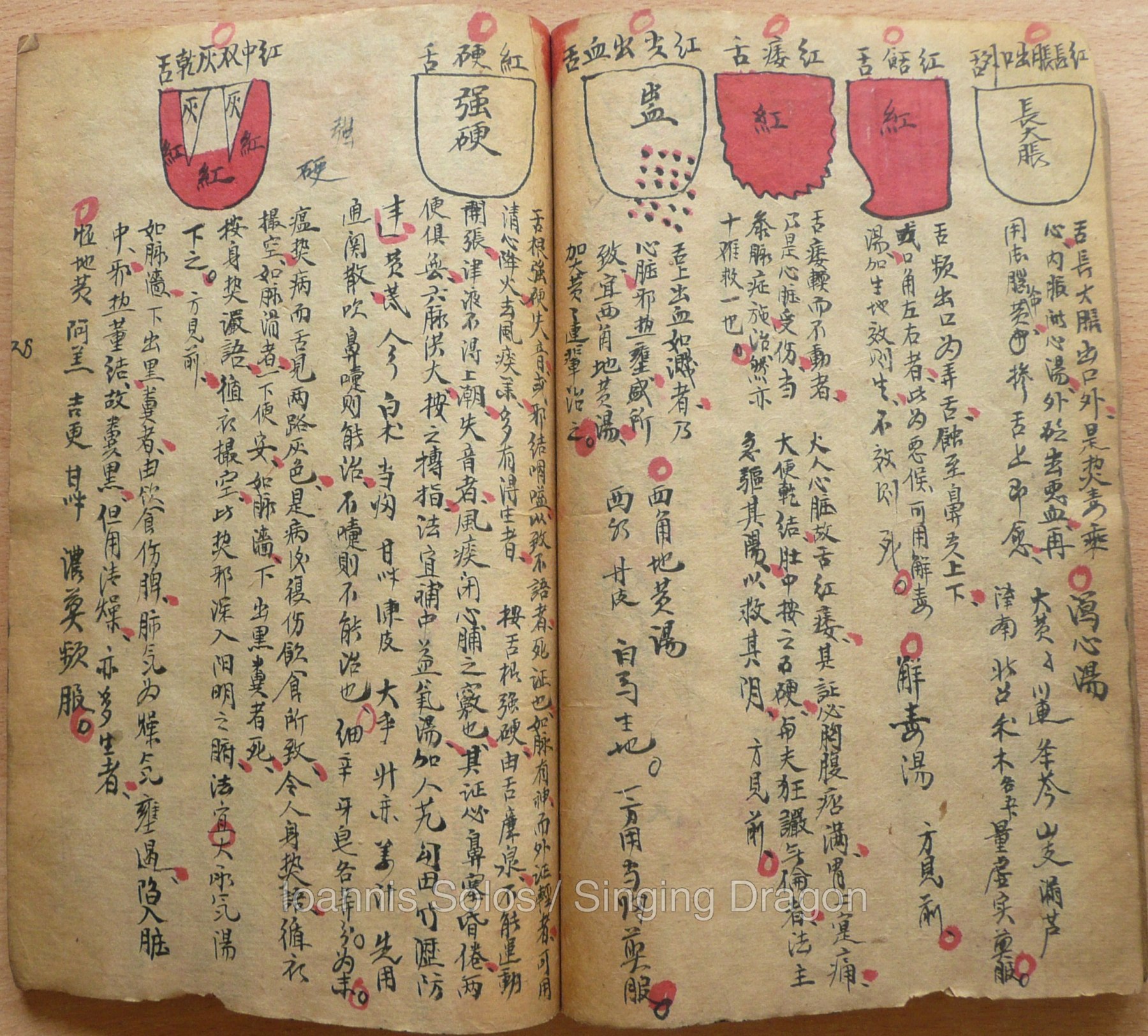

A handwritten version of the “Tongue Reflection in Cold Damage” with coloured illustrations. This variation also fully presents the structure of the formulae mentioned in the text, in accordance with the tradition in “Scholar Ao’s Gold Mirror Records”. Late Qing or early Min Guo manuscript.

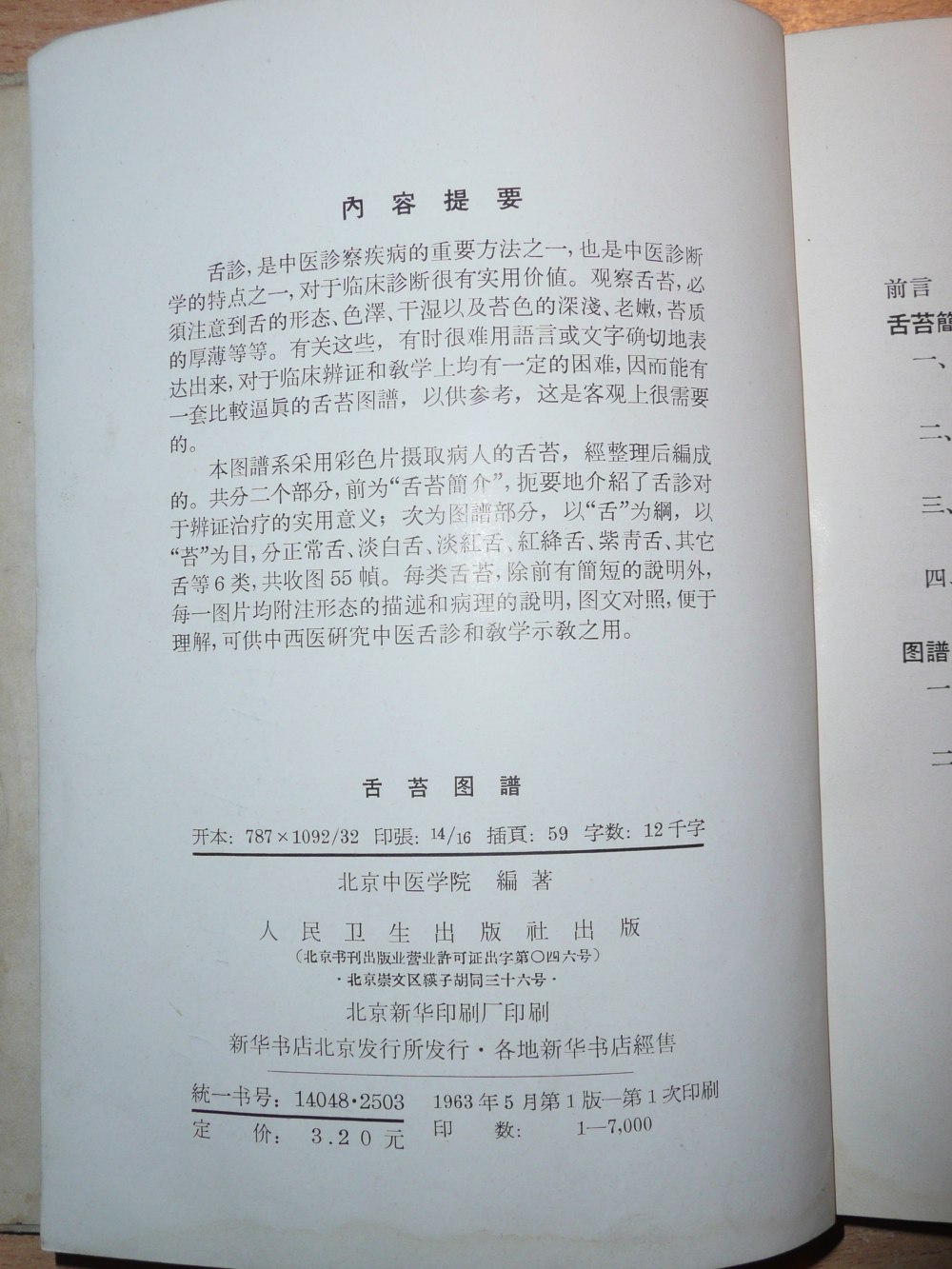

The Tongue Reflection in Cold Damage (Illustration 3) was much simpler and easier to use, and it was reprinted continuously until the 1960’s, when it was finally replaced by modern tongue manuals.

To summarize, the Scholar Ao’s Gold Mirror records and the Tongue Reflection in Cold Damage have intimately influenced the development of modern Tongue Diagnosis, and they are still regarded as the core materials for exploring the theory of tongue diagnosis in depth.

These days, I believe that in order to better facilitate the westward transmission of Chinese Medicine, scholars should present complete ideas about their specialty, and provide a functional understanding of both the content and the history of their chosen field. In my opinion, the best way to accomplish this is not by randomly translating famous books or by providing many alternative translations of the same texts over and over again, but by presenting collections of important manuscripts arranged in such a way that can clearly demonstrate how each branch of TCM was developed.

In my humble book the Gold Mirrors and Tongue Reflections, I provide a translation of both the Scholar Ao’s Gold Mirror records (Ao Shi Shang Han Jin Jing Lu) and the Tongue Reflection in Cold Damage (Shang Han She Jian).

Having been researching classical tongue diagnosis for nearly a decade, I now wish to present my modest collection of influential tongue monographs, not only with the publication of this book but also through a companion volume currently in progress. I hope that my work will positively contribute to the further development of tongue research in the west, and assist my fellow TCM practitioners to develop a proper understanding on the academic origins of Tongue Diagnosis before accessing modern manuals.

All illustrations come from the author’s private collection of tongue manuscripts.

© 2012 Singing Dragon blog. All Rights Reserved.