One of my mentors developed some quite interesting ideas. Much as I’d like to share them specifically and credit him, he and his wife long ago decided that to keep his message pure, they didn’t want him quoted or credited, because they feared his work and ideas would be misrepresented. So, sort of like the reverence with which I hold MY interpretation of John Pierrakos’ work in CORE Energetics, I’d like to share a bit of MY interpretation of a different take on neck pain, fuzzy headedness, and poor health in general. I’ve sprung forth from the wisdom of the unnamed mentor.

One of my mentors developed some quite interesting ideas. Much as I’d like to share them specifically and credit him, he and his wife long ago decided that to keep his message pure, they didn’t want him quoted or credited, because they feared his work and ideas would be misrepresented. So, sort of like the reverence with which I hold MY interpretation of John Pierrakos’ work in CORE Energetics, I’d like to share a bit of MY interpretation of a different take on neck pain, fuzzy headedness, and poor health in general. I’ve sprung forth from the wisdom of the unnamed mentor.

We’ve all heard the term “Get your head on straight,” and most of us can see or feel how our heads live too far forward, in front of the rest of our bodies. Many of us use bodywork, postural work, or other awareness therapies to help us hold our heads high and keep them there. It’s not easy! Between driving, sitting in cars and recliners, pursuing intense close detail and breath-holding work (as a hobby or professionally), or for any of a hundred more reasons, we tend to sit and stand with our heads in front of our trunks and hearts, instead of allowing the heart to arrive first and the head to ride on top.

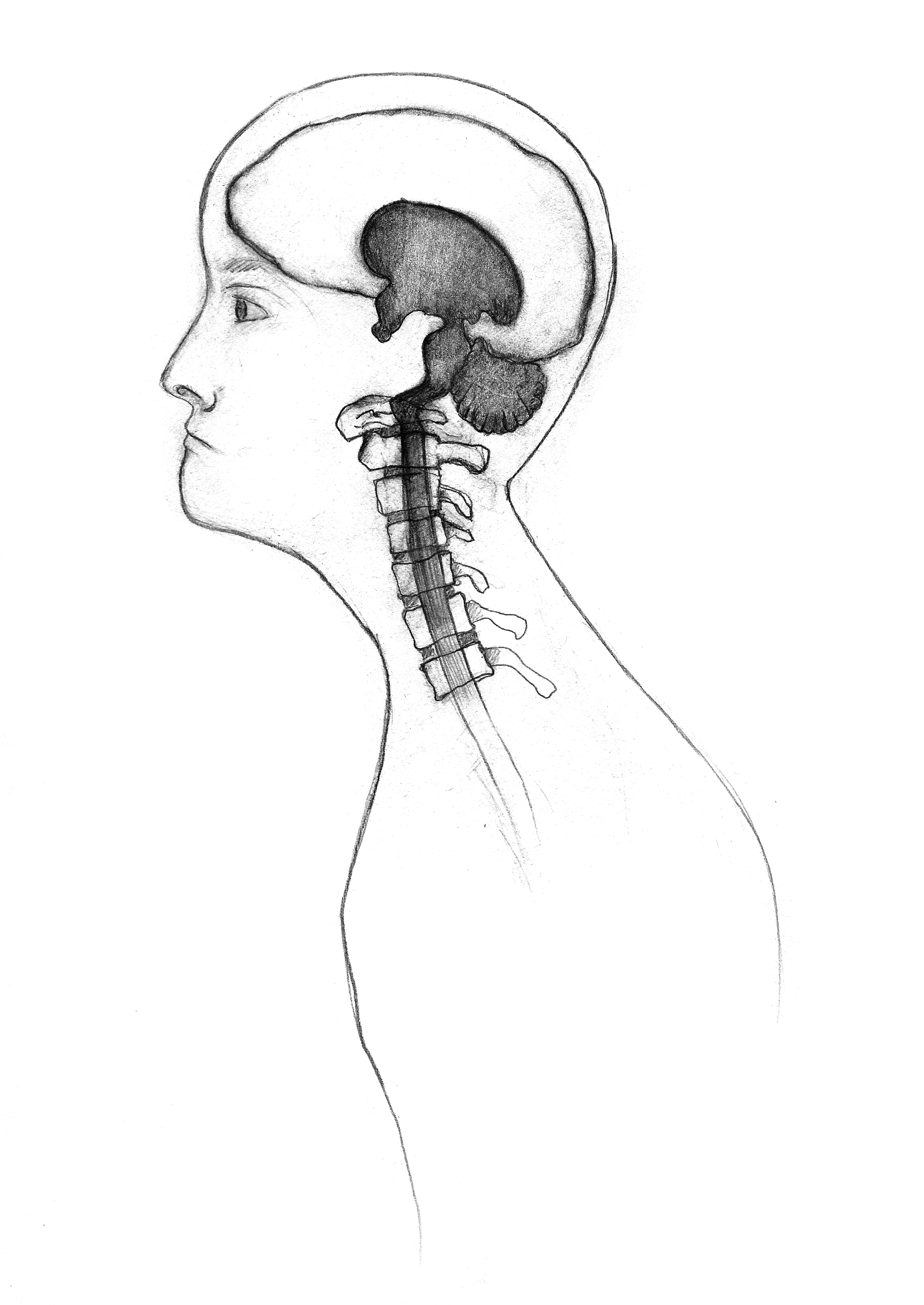

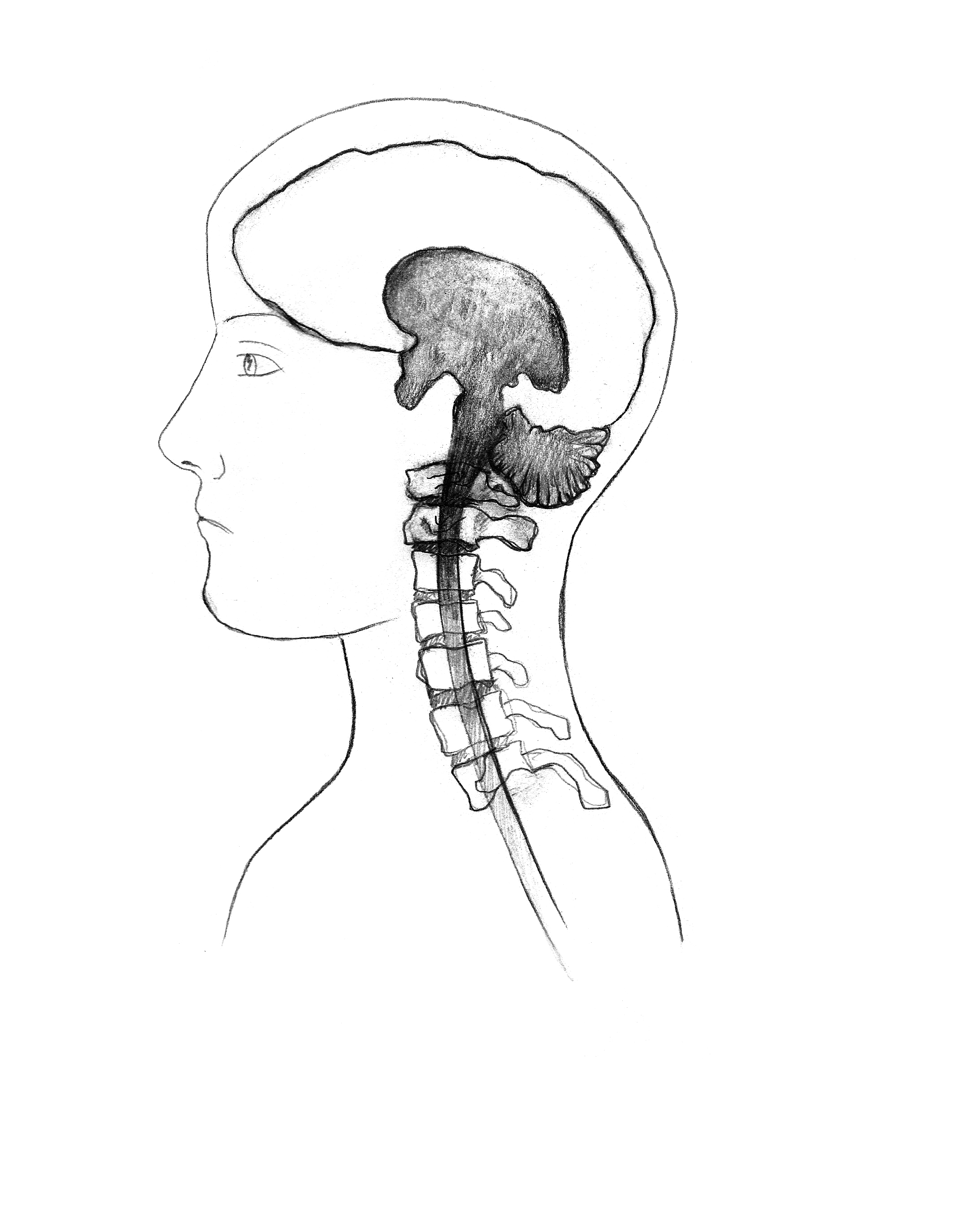

Let’s examine the bones involved here, namely the cranial bones including the occipital bone right at the back base of the skull. Just below it we find the seven cervical vertebrae or spinal bones. Imagine these seven have fingers on each side of the main body, and a little tail at the back of each, with muscle tissue running in every direction to/from all of them. Any one of these bones can get jammed/shortened/twisted in a way that nerve impulses leaving the spinal column above or below that bone get slowed down. It’s hard to send the full message through a clogged channel. As these cervical bones gets out of line, not only the neck, but the head, shoulders, and even arms and wrists can suffer. So, how do we keep the head on straight?

This mentor believed that demons and entities attached themselves to us, right at that place on the back of the neck where skull and neck meet. He claimed the physical sensation generated by these psychic attacks caused the first cervical or atlas bone to move forward, further jamming the spinal column, with the occiput and the axis bone immediately below the atlas pinching this atlas forward and tight.

I never particularly liked the language of demons and entities and for years I simply thought of these ‘energies’ as negative thought forms. After all, if they’re shortening and tightening your neck in a way that deprives your brain of energy, aren’t they negative? In the last couple of years I’ve been reassessing that term and now call these energies ‘unresolved’ thought forms. To me, I’ve therefore assumed responsibility for that which is occupying my space; even if it was directed at me (positively or negatively) by someone else. I believe in trying to take the ‘negative’ out of the situation and working instead at resolving the thought form in the mental and spiritual realms before tackling the physical body.

To that end, ask a client to sit, stand, or lie straighter or longer with chin down, back, and into the chest while the back of the neck pushes straight back; then to breathe. While they breathe I encourage them to allow angers and anxieties to leave even before I apply gentle neck traction. Then, with all these pieces in place, I believe we do the work of helping clients find their true north, their ‘up’. As they physically allow opening, some of the unresolved thought forms can move themselves. Or, as they work to release unresolved thought forms, won’t the neck feel looser? Won’t blood and nerve supply nourish the brain and suddenly make thoughts clearer?

It’s simple; it’s not easy!

© 2012 Singing Dragon blog. All Rights Reserved.