Leonie Taylor & Charlotte Watts explore how our skin is the first line in communication, both to our internal landscape and the world around us.

The integumentary system (aka the skin)

The integumentary system, otherwise known as our skin, is both a boundary and a contact surface, a sensory organ. Every inch of our skin hosts over 2.5 million bacteria. The make-up of the skin microbiome varies greatly between individuals as well as where on the body it is, influenced by:

- Physiology: sex hormones, age and site

- Environment: climate and geographical location

- Immune system: previous exposures and inflammation

- Genotype: susceptibility genes

- Lifestyle: occupation, hygiene

- Pathology: underlying conditions

Skin is constantly sensing what we come up against and assessing how we feel about it. The casing of our skin is our embodiment, how we move in relation to the external world, how we relate to others and the emotional tones we then process internally. This is a reason to practice yoga in bare feet, where we can engage with a sensory relationship, ground and connect to what is coming up from our environment.

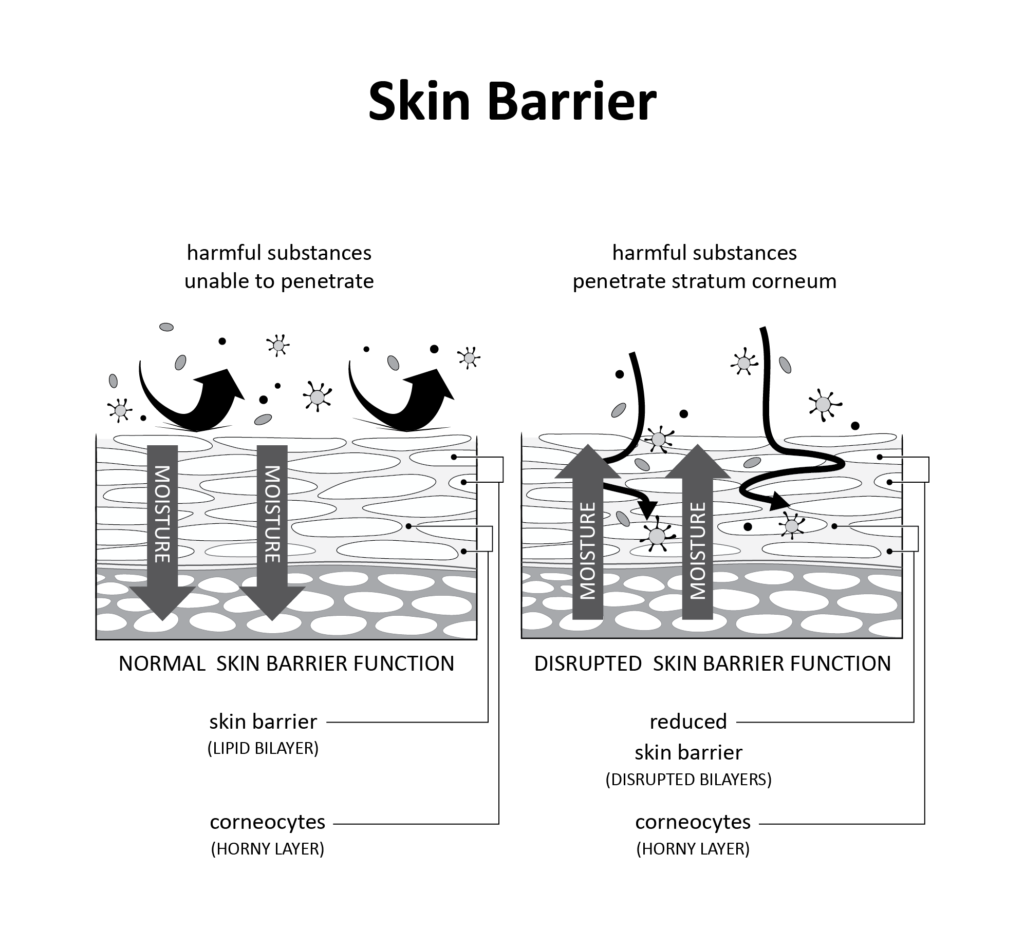

Dysbiosis (bacterial imbalance) in the skin microbiome is similar to leaky gut syndrome (gut permeability), where the gut’s surface allows substances into the bloodstream between cells, rather than going through them. This means that our boundaries become permeable where they should protect, a common route for intolerance and compromised healing, inflammation. Toxins, stress, processed sugar (which feed unhealthy bacteria), too much alcohol and sanitising products can disrupt the healthy functioning of our microbiome as boundary.

How we sense through the dermatome

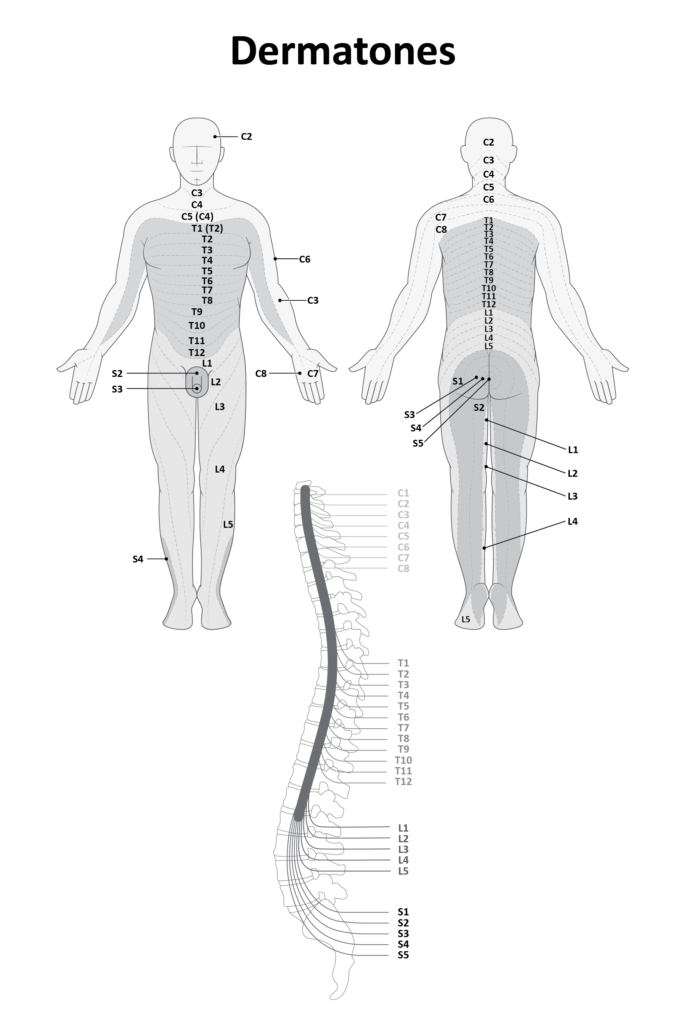

The dermatome is an area of skin supplied by nerve fibres reaching from a dorsal root of spinal nerve, which relays sensation from a particular region of skin to the brain. Our relationship to the outside world via skin contact feeds back into our centre via the somatic nervous system (SNS) and into the central nervous system (CNS). In somatic practises, rubbing, rolling and changing pressures onto our external body help the process of making sense of the outer world by creating clear sensory feedback that we can consciously affect and play with. This sensing of the periphery links back into our immune responses.

Our microbiome as communicator

Our microbiome is the microbial life that populates both out skin and all the interior surfaces of our mouth, digestive tract and gut. A healthy microbiome is an important part of our innate immunity, a physical barrier against the entry of toxins and harmful organisms and intrinsic to the process of replenishing the linings of the gut and skin, replacing damaged and dying cells.

There is a parallel between the microbiome’s relationship with our bodies and the connection in yogic philosophy between the individual self and universal consciousness. We are not separate from our environment and interconnected with everything. The consequences of our increased separation from nature and each other, exacerbated by factors such as stress, sugar excess and over-washing, impact negatively on our microbiome. Yoga practices that foster embodied awareness bring us back to soma – first person, phenomenological experience – rather than third-person, ‘what’s wrong, let’s fix it’ – and allow us to retune into that symbiosis with which we evolved. Yoga helps us to modulate and adapt to stress, positively affecting inflammatory markers.

Sensing in and out

Proprioception is how we meet and respond to the world. Information from outside of ourselves moves through the skin, fascia, muscles and joints to the spinal cord and brain, through proprioceptors (sensory nerve endings) in fascia. Our understanding of the role of fascia within the somatic nervous system is in its infancy.

Interoception is how we sense inwardly, gauging how internal sensations relate to our emotions, reactions and movements that affect behaviour. As one of the first lines of sensory perception, our skin is our outer edge, where our outer and inner worlds connect and communicate into our gut, and are then translate back out into how we respond to the world.

Interoception has been linked to pleasurable touch and sensuality: interoceptive C-fibre endings on skin trigger a sense of wellbeing, yet for some with disordered relationship with touch, this can also register as a tickle to withdraw from or even pain. When we are in healthy relation with others, these receptors form a system for social touch and skin-to-skin contact that is of profound importance to health.

Mobility through the tissues into the organs

Movement relies on mobility in tissues – skin, muscles, fascia, nerves, blood vessels, ligaments and bones – as well as the organs. Any tightness creates a pull and in the case of viscera, this pull is from the centre of the body, which affects how we reach outwards. Our body is continually repairing, and it is common for scar tissue (as disorientated fascia) to form as we age. Some of this won’t have any noticeable effect, but it can distort the movement of the gut and pull the small and large intestines out of the best functional placement, contributing to pain, inflammation, bowel obstruction and constipation. This lowered visceral mobility can present as digestive symptoms such as IBS, gas or belching, but also referred pain around the body.

Yoga and somatic practices help us not only to explore more fluidity of movement but also to increase our sensory awareness, exploring the relationship of touch – between our bodies and the floor/props and between different parts of our bodies (eg: an arm resting on a thigh or thighs drawing in to the belly) – moving between sensing outwards to receive information internally. As we reconnect our internal and external landscapes, we return to a state of yoga, union, wholeness.

Practice:

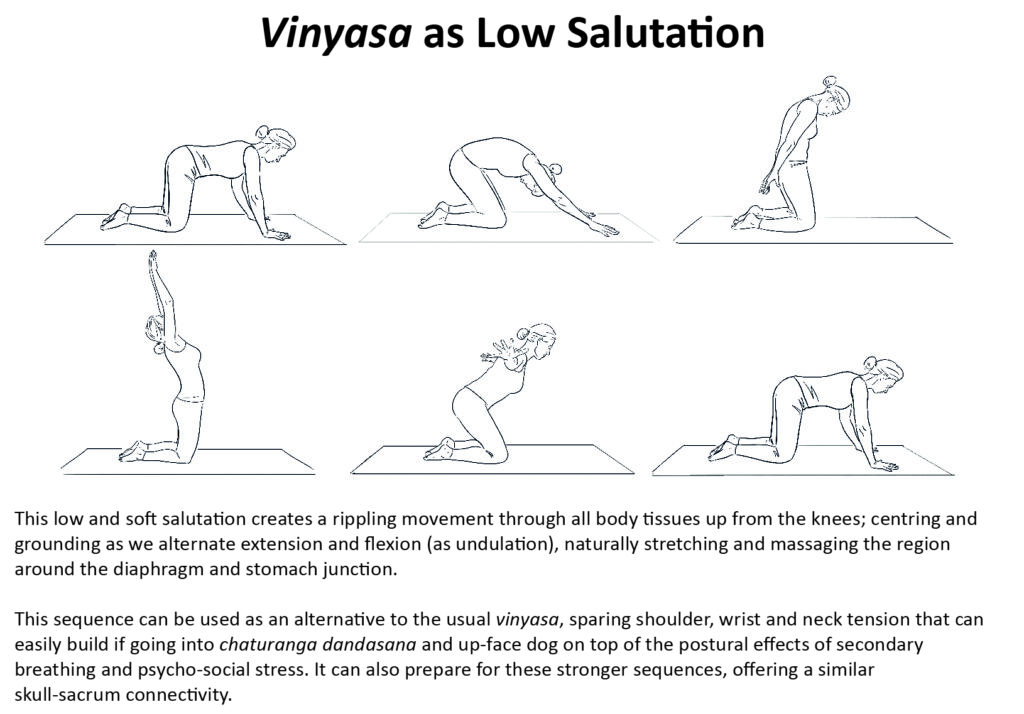

Low-salutation Vinyasa

This sequence has similarities to some versions of a moon salutation (chandra namaskar) as it stays lower to the ground. Exploring movement up and away from the floor, we expand the boundaries of the body in a smooth, spacious, steady way, drawing back towards the floor.

- From all fours, folded blanket under your knees if needed, wriggle your hips and shoulders to loosen your joints. Feel the belly area between your hip bones and lower ribs, where the movement comes from.

- Drawing your belly into your spine, drop backwards, rounding your back to drop your head and draw the weight off your hands.

- Continue drawing the belly back and up, to raise up onto your knees, up through your inner legs, spine and neck, taking your arms out and up, rolling up the front body, looking up to the extent that your neck is comfortable.

- Bend at your hips and drop your bottom back, spine lengthening, arms back out and down. Engage the ‘square’ of your belly between your hips and lower ribs to support your lower back and come back to all fours.

- Continue the sequence at an easeful pace, staying to hold and breathe fully in any position that needs exploration and opening.

Feel the relationship between your skin meeting the ground, the breath travelling into your body and meeting your interior – the interdependence of internal and external.

For a deeper dive, see Yoga Therapy for Digestive Health and Yoga and Somatics for Immune and Respiratory Health.