…And how yoga – both physically and philosophically – can ease the path to healing

By Leonie Taylor & Charlotte Watts

From content covered in their books Yoga Therapy for Digestive Health and Yoga & Somatics for Immune & Respiratory Health.

To talk ‘health’ in a modern context is to recognise the need to be ‘trauma-informed’ and meet the recognition that we are all holding the stories of the past in various ways, much of which is unconscious and comes out in reactions that may overwhelm or that we don’t understand. This is not to teach a specific ‘trauma class’, but to be aware of holding compassionate space for the subtleties that tuning in and embodiment can uncover.

We don’t need to identify or even mention trauma but whether teaching a class or holding space for ourselves, recognising that tuning into our needs, boundaries and responses is to allow any nature of experience to arise. Whether we are holding intergenerational, shock, developmental or vicarious trauma, embodied awareness (tuning into the sensory, bodily experience of each moment) can help us navigate towards a relationship with grounding and even calm. It may even be the gateway towards post-traumatic growth.

Psychoneuroimmunolgy (PNI) is the study of the interaction between psychological processes and the nervous and immune systems and takes an interdisciplinary approach. Where modern, reductionist science removes the dirty business of emotions from the ‘mechanics’ of the body, more systemic and even quantum viewpoints show our whole-life experience not only effects but is never separate from the all-body-mind-system expressions and how these might manifest as dis-ease.

This is epigenetic, so not genetically predisposed, rather shaped by our life experiences, which fits perfectly with the yogic model of samskaras – learnt behavioural habits. Trauma is a large player in cultivating this internal landscape and how it plays out on our behaviours.

Trauma and our gut

From a PNI perspective, trauma is not something outside of disorder or symptomology, which provides a framework to reconnect with the whole, as we practise within yoga. Rather than fixing or solving something that is broken or wrong, we can explore reintegration, the ‘union’ of yoga, nurturing the whole being to holistic health and healing: holism.

Trauma has historically been categorised and treated psychologically, with labels such as:

- Post-Traumatic Stress Dosorder (PTSD)

- Acute stress disorder

- Depression

- Anxiety disorders (eg panic attacks, OCD, addictions and eating disorders)

- Borderline personality disorder

- Dissociative disorders

For those with trauma, these responses are the only way their more primal, instinctual responses can make sense of the present. There is no space for reflection in a state of hyper vigilance, and we act from immediate, protective, gut-to-brain instinct.

The definition of trauma has expanded to include anything that overwhelms us to the point of being unable to cope. When we view trauma from a more mind-body, non-reductionist way, any trauma, stress or life event is wholly physiological, including the mind. Within yoga philosophy, what happens in the body happens to the mind and vice versa.

Developmental Trauma (ACEs)

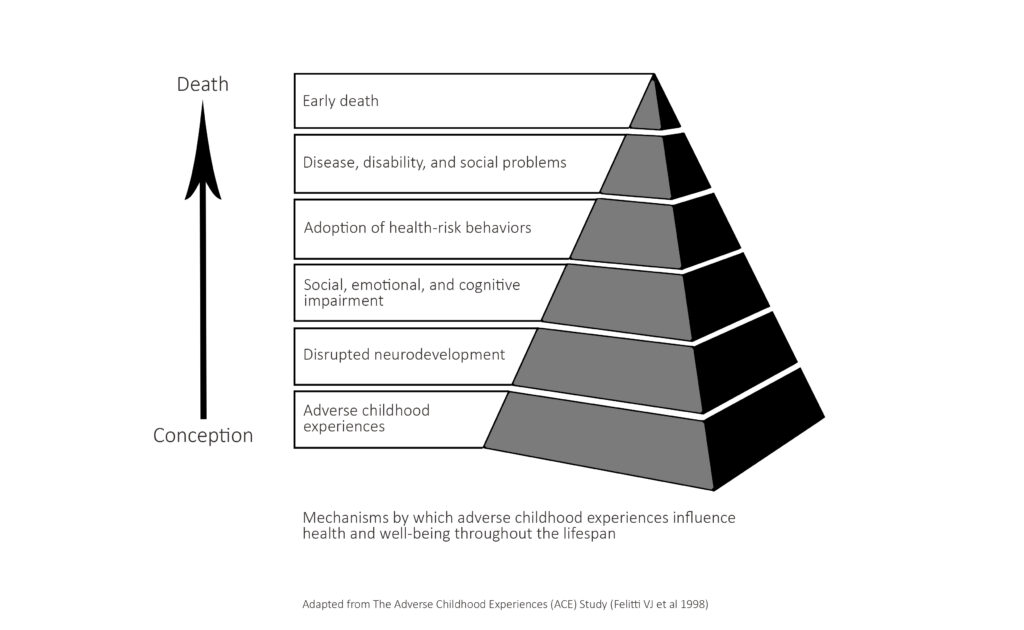

Developmental trauma is also referred to as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) from the extensive 1994 study (see diagram below).

These can be recurring painful situations or experiences such as:

- Criticism

- Childhood neglect

- Bullying

- Experiencing addiction, mental or medical illness in the family

- Lack of healthy attachment or attunement in early years

This is not to identify or diagnose trauma, but to be aware of the conditionings and drivers that can surface in a survival response to a time or event from the past. Allowing these to be present – with compassion and without reaction or judgement – can offer a route back towards post-traumatic growth and the regulation within body systems that gets lost.

While young brains are developing, if there are ACEs, the emotional centre – the amygdala within the limbic system – learns that increased fear reactivity is essential for survival. This state maintains inflammatory tones, lowers digestive function and disrupts adrenal output and hormonal function.

This dysregulation can show up as:

Physical symptoms, eg:

- Inflammatory disorders

- Autoimmune conditions

- Respiratory conditions

- Related digestive issues

Emotional symptoms, eg:

- Depression and fear

- Anxiety and panic

- Numbness, irritability, anger

- Avoidance

Cognitive symptoms, eg:

- Being easily distracted

- Memory lapses

- Indecision

- ‘Daytime fog’ associated with high cortisol

Behavioural issues, eg:

- Compulsion

- Substance abuse

- Sexual disruption

- Impulsive, self-destructive behaviour

Resetting the vagus

We come to self-soothing via the vagus nerve – the 10th cranial nerve that comes out of the skull down into the organs. This has the opposite effect and function of the stress response, a ‘reset’ after a stressor has passed, where we move from reactive to reflective states, the body can calm, rest, digest, heal and detoxify.

For someone with trauma, the greater the perception of threat escalates, the more their body will default to reactive and vigilant primitive responses, with less and less consciousness. Through gentle, somatic explorations, grounding, embodied awareness, it is possible to reorient and socially engage, moving back towards post-traumatic regulation.

We can access the vagus directly behind the eyeballs and in the palate of the mouth, tongue, ear canal and lobe, and surface of the lips Which is why the invitation in yoga classes to ‘soften your eyes, face and jaw’, breathing into and bringing attention to these areas releases tension.

Tuning in to the body’s deeper wisdom through meditative, embodied practices, can unlock deeply-held trauma

- Environmental stressors and physiological or emotional threats provoke reactivity in the body, where it will manifest as muscle tension, granthis (knots) or the development of unhealthy habits.

- All experience in the body is impermanent.

- Traumatic experiences held in the body can be triggered and re-experienced as feelings, sensations and memories.

- The body, as the mind, has plasticity, constantly changing and remoulding.

- Healing and self-repair is possible at any point.

- Practising non-judgemental awareness, compassion and patience create the perfect environment in which the body’s innate wisdom can arise.

- The body is the route to deep healing and transformation of emotional trauma.

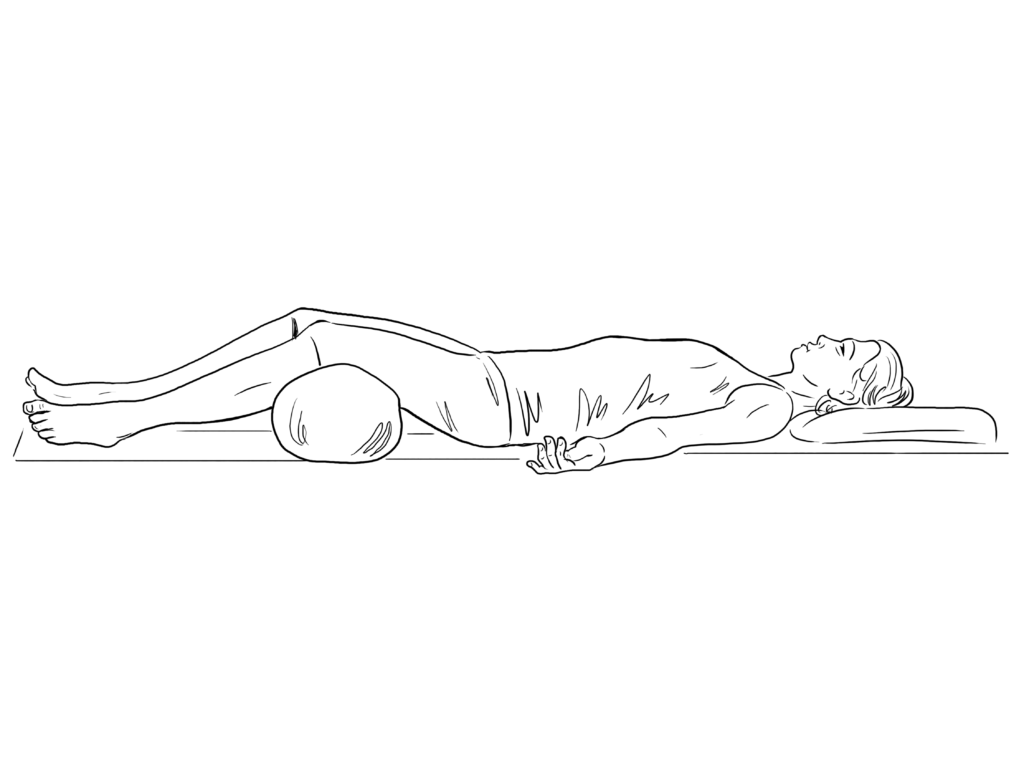

Savasana (Corpse Pose)

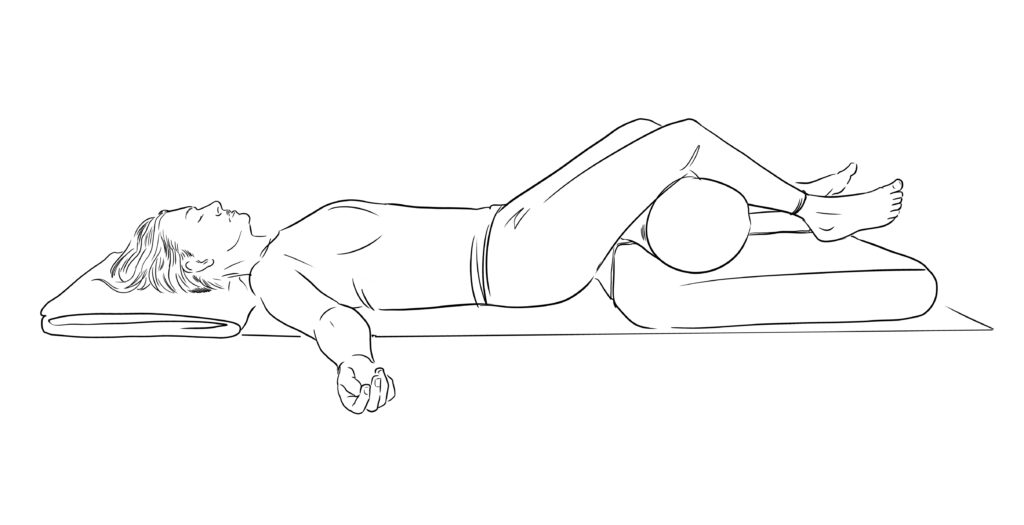

When we lay on the ground, whatever is closer to it tonifies and what is above opens to the sky, softens. A daily 20-minute practice, where we can stay in that limbic space between awake and asleep, can provide the balance between time spent in parasympathetic tones with enough sympathetic to remain awake so that when we come to we are refreshed. This is like a ‘conscious nap’ – awake and attentive but with space to down-regulate heightened states.

Savasana variations with lift under the knees; with raised legs; side-lying

Soothing considerations:

- Take time to cover yourself with blankets to feel cocooned and safe

- Find the place where the wrists can fully drop and the fingers can lightly curl to offer passive ‘not doing’ with the hands.

- Transition slowly our of Savasana as those with trauma can have the tendency to be startled out of this unfamiliar resting place. Learning to trust and experience moment-to-moment, coming back to the world easefully, can be a profound practise.

In both Yoga Therapy for Digestive Health and Yoga & Somatics for Immune & Respiratory Health, we explore how yoga teachers can create trauma-sensitive spaces and practises.