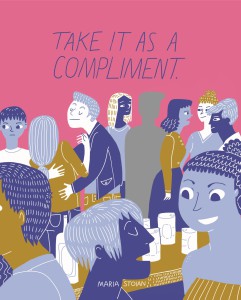

Bringing together the voices of males and females of all ages, the stories in this collective graphic memoir, Take it as a Compliment, reflect real life experiences of sexual abuse, violence and harassment. In this blogpost, Maria Stoian explains the thinking behind this important graphic memoir, published by Singing Dragon.

Before I can talk about Take it as a Compliment, I feel I should introduce the project which preceded it. It was a short comic called The Elephant in the Room, which I made during my undergraduate degree. It was a fictional story exploring how the trauma of sexual assault might affect a person’s perception of reality and how they might deal with it in their daily life – which is to say that they probably would not talk about it, but instead bottle it up.

The project ended up being something I talked about all the time, and, as a consequence, the subject of sexual violence came up frequently. One day, I mentioned a comment I had read online which said, “When I finally plucked up the courage to tell my mother about my rape, the first thing she did was ask me what I was wearing.” I thought this was a horrifying response, in its words and also in how common the sentiment it expressed is. Instead of being appalled, however, one of the girls I was with said, “Well, a woman is responsible for her dignity.”

I couldn’t believe that the testimony of this girl wasn’t enough to convince this girl – that it didn’t say enough. I thought, “This happens to so many people, how have you missed this?”

The much more common response to my project was that people started sharing their stories with me. There was a lot of, “Oh, this happened to me too” or, “This reminds me of something else I’ve experienced” or, “I haven’t talked about this before, but now i feel like I can.””

All this made me think that if I were to draw up all these stories and put them in a book, it would speak to people when they read it. It would speak to them so loudly, and so clearly that it couldn’t be ignored by people who thought that the source of the problem was women’s lack of “dignity.”

When I started collecting stories, it was definitely a group effort. I didn’t have a very prominent web presence, so my friends helped me get the ball rolling when they told their friends about the project, and when the feminist society at uni posted a link sending people to the project’s blog, that was a huge help as well. I ended up with anonymous Tumblr messages, emails, and even a few interviews.

Each story is stylistically a bit different as a result of each voice being different. I received stories that were several pages long, and some that were only a couple of sentences. There are chapters where the narration is there, word for word, and there are also stories that only include dialogue. I found the responsibility of telling the story as truthfully as possible – often without knowing the protagonist – to be a bit difficult. Some people were very frank about what had happened to them, to the point where they were just recalling a series of events. Others talked about how they felt, and that was when I had to decide whether to show it, or use their words.

Each story is stylistically a bit different as a result of each voice being different. I received stories that were several pages long, and some that were only a couple of sentences. There are chapters where the narration is there, word for word, and there are also stories that only include dialogue. I found the responsibility of telling the story as truthfully as possible – often without knowing the protagonist – to be a bit difficult. Some people were very frank about what had happened to them, to the point where they were just recalling a series of events. Others talked about how they felt, and that was when I had to decide whether to show it, or use their words.

I also thought a lot about how I would be designing the characters. I had never met most of the people who shared their stories with me, and the people I did know needed to not look like themselves, while still being themselves. I didn’t want the audience to read the characters incorrectly; I wanted to convey the sense that they were all just everyday people.

To make a point about how I was thinking about the problem, I simplified it in a little exercise for my classmates. I made a small activity book and among the questions I had prepared, I asked the readers to make judgements about the characters I drew, to assign personalities to them, and to label them as heroes or villains. The idea was that, in real life, there are no guaranteed visual signs for what a person is like, and any interpreted signs are based on what we have been taught by culture and the media. The responses I got were that it was difficult to say which character was what, because they all appeared neutral – and yet there were clear patterns in how people judged the faces. After I explained, “Of course they just look neutral, that’s what real life is like, that was the point.” I was advised to draw the characters more “good” or “bad.”

The frustration that people felt when the characters didn’t fit into neat two-dimensional boxes was something I thought might come out of Take it as a Compliment. While I wanted each story to have its own individuality, and show each character’s humanity, I also wanted it to have a certain level of neutrality, a sense of this individual human being and their unique experience being one of many. I learned that statistics didn’t say as much to people as I thought they would. It seemed everyone already knew the 1 in 6, 1 in 4, 1 in 3 estimates from this study and that one. Somehow it wasn’t enough, it didn’t translate perfectly that the 1 was a human being. And equally, that what happened to them was caused by another human being. Survivors and perpetrators of sexual violence are real, everyday people.

As it turned out, the anonymity ended up not being that important to all that many people,  what with there being interviews and emails sent. Not only did people choose to approach me without anonymity, some people even signed their names to their stories. One person introduced themselves in their written story by name, saying, “And that’s my REAL name, because these things happen to REAL people.”

what with there being interviews and emails sent. Not only did people choose to approach me without anonymity, some people even signed their names to their stories. One person introduced themselves in their written story by name, saying, “And that’s my REAL name, because these things happen to REAL people.”

All throughout its creation, I thought of Take it as a Compliment as being for two groups: For survivors and for bystanders. For the survivors, I’d hoped that the act of telling their stories would be part of a sort of healing process for them. And for bystanders, it was a message to be active in the discussion and to take action regarding the issue.

I don’t know how much personal benefit the survivors in the stories got from sharing, but it was clear that many of them did it not for themselves, but out of a concern for other people. Almost every contributor prefaced their story with something along the lines of, “People need to know this is a very real, and a very common occurrence.”

I think one of the most exciting things about the book getting published is that the survivors who did choose to remain anonymous have a chance to see that it became a real thing, and that it’s part of a conversation. Before Take it as a Compliment was picked up by Singing Dragon, it really was just all the stories, back to back. That was the main thing that needed to change. The publisher really felt – and I agree – that there needed to be a conclusion. A lot of people might get through the book and feel a lot of anger, and rightfully so. They might also feel helpless. But there is a lot of power in the discussion. There are a lot of us out there who are aware of the issues and who are eager to make changes.

My hopes for Take it as a Compliment going forward would be for it to keep doing what it’s been doing, which is to keep the conversation going. Even after the project was finished, and it was on display at my university’s grad show, I was approached by an older woman who said, “I really connected with your project because I’ve also been raped. Thank you.”

When we stand up and talk about these experiences, we can make more of an impact together, than we can by suffering in silence on our own.

Maria Stoian is a graphic designer and illustrator based in Scotland. She is interested in the way illustration and games can be a non-aggressive way of encouraging people to recognise when they might be biased. Take It As A Compliment was Maria’s Master’s project at Edinburgh College of Art.

Take it as a Compliment by Maria Stoian is AVAILABLE NOW

Take it as a Compliment by Maria Stoian is AVAILABLE NOW

Price: £14.99

ISBN: 978-1-84905-697-7

1 Response