How we breathe effects every system in the body, from our energy and stress levels, our focus and creativity, to our immune and digestive health.

By Charlotte Watts and Leonie Taylor, co-authors of Yoga & Somatics for Immune & Respiratory Health

Pranayama, yogic breathing, means ‘extends life force’. This points to the importance of the breath to our whole health; healthy breathing patterns not only support respiratory health but also affect our immune capacity. This in turn affects our digestive and whole body health.

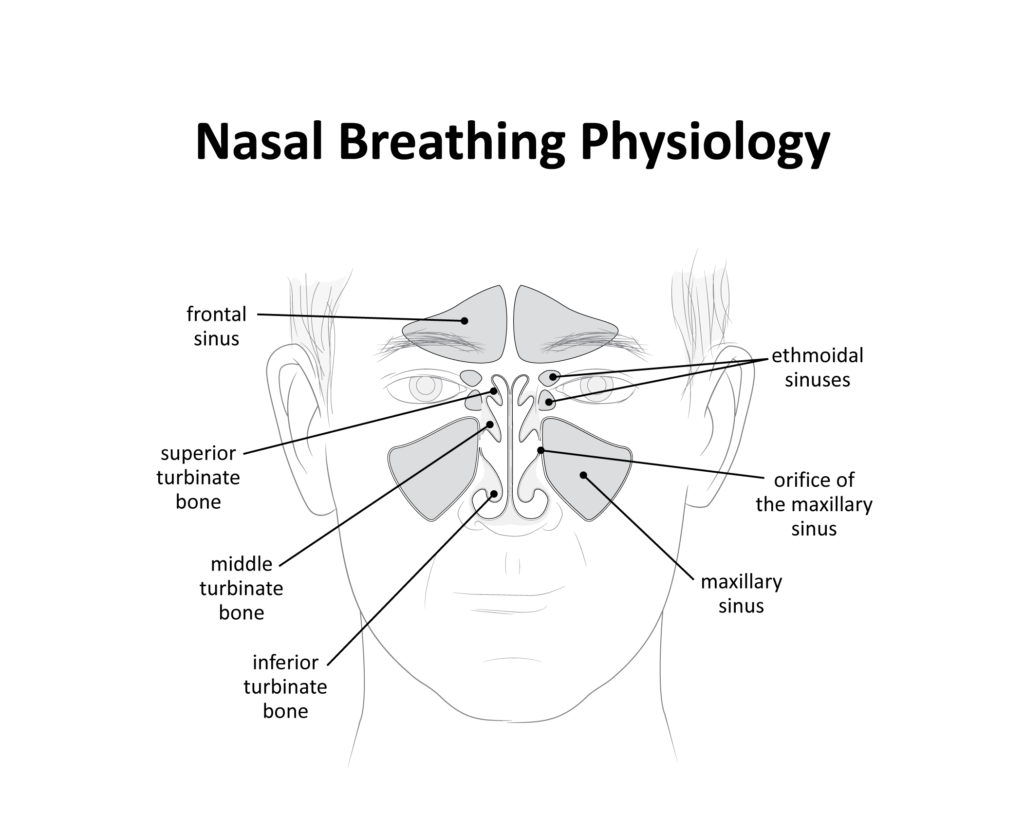

Many people now have respiratory, immune, digestive and nervous system problems, but it is often not diagnosed or linked to the difficulty with nasal breathing that can be at the root of it all. But why is nasal breathing so important?

The benefits of nasal breathing:

- Supports soothing via healthy vagus nerve function (vagal tone) as it is evokes parasympathetic responses (brings down stress): helps us drop into calm, relaxed states.

- Protects health of tissues in the mouth and the microbiome there – key for the oral health that affects all body systems.

- Tiny hairs in nose filter air coming in of pathogens – it is our first line of immune defence.

- Cool air coming through the nose cools the frontal lobe of the brain, calming activity.

- Produces nitric oxide which supports absorption of oxygen, better carbon dioxide exchange and release, and improves blood flow. This protects the immune system and helps maintain body wide homeostasis (balance).

- Uses less exertion than mouth breathing, translating as better performance and shorter recovery time in exercise.

We can see from this that nasal breathing is hugely important. Physically, nasal breathing engages the whole breathing apparatus: more diaphragmatic movement, the lower lungs and rib cage moving to massage the heart and lungs. Full rib activation acts as a pump to pull lymph from the lower body up to the chest and heart, promoting better circulation and immune protection. This is crucial for the full range of motion and flexibility through the spine, head, neck and lower back, and if we have that capacity, our posture is supported, feeding back into the breath: like so many aspects of optimal function, this is cyclical. Nasal breathing supports how we move to support nasal breathing. Where there is interruption, we can get caught in vicious cycles of immune and respiratory imbalances.

In terms of our nervous systems, nasal breathing improves alpha brainwave coherence, which is related to more peaceful, meditative states, which can elevate mood and increase creativity. This can also affect our ability to socially interact, our emotional stability and self-confidence. Nasal breathing is said to be related to a significant reduction in sympathetic and high limbic, ie stress, states, which impacts our immune and respiratory health.

The problem with mouth breathing

Habitual mouth breathing bypasses all the important stages of the breathing process. This can lead to several issues. We can lose 40% more water at night by mouth breathing, which dries out mucosal lining airways, leading to:

- Malocclusion (misalignment between upper and lower teeth)

- Oral hygiene problems

- Asthma

- Snoring

- Sleep apnea and disrupted sleep patterns

- Gatrointestinal disorders

- Inbalance of hormones

- Lack of oxygen to the brain – effecting growth, even intelligence, as well as energy levels, and associated issues such as attention deficit disorder (ADHD), diabetes, high blood pressure and cancer

- Sympathetic dominance

Difficulties in nasal breathing may be postural as well as stemming from repeated stress responses. Evolutionary shifts in the shape of our skulls and the size of our brains has effected how we breathe and societal and environmental shifts post-industrialisation, how we work, has affected our posture. Habitually pushing the head forwards of the spine and jutting the chin out, often evolving from sedentary patterns, causes more tension in the throat and impedes free flow of air.

As well as posture, nasal issues leading to mouth breathing can include:

- Deviated septum

- Broken nose

- Excess mucus (this can be caused by diet, dehydration or inflammation)

- Enlarged tonsils or adenoids

- Polyps

- Poor immune modulation around upper respiratory area manifesting as hay fever, sinusitis, rhinitis, asthma or allergies

Habit is also an important factor in mouth breathing. We can get stuck in this pattern when we tend towards sympathetic dominance, constantly doing, alert, where we become familiar with that tone of the nervous system and it is registered as ‘safe’, rest, ironically being perceived as less so. Many avoid rest, slower forms of yoga or meditation for this reason even though it is what is most needed.

Consciously repatterning the breath

Patiently retraining our samskaras, or habits, through pranayama practises, consciously paying attention to our breath, we can, over time, help to overcome patterned mouth breathing. The majority of pranayama practises are nasal and encourage expansion of the whole respiratory system to support mental and physical vitality.

Nadi Shodhana

Traditional alternate nostril breathing involves hand manipulation of the nostrils to restrict the breath, but a visualised version is very calming for the nervous system and can be done lying or sitting comfortably.

- Whether lying or sitting, find a position where you are supported and can breathe easily

- Settle into the natural flow of the breath into the belly

- Imagine inhaling through the right nostril then exhaling through the left. Then inhale through the left, back out through the right. Move your attention side to side.

- After a few rounds, stay sitting or lying for five-10 minutes to assimilate the practise.

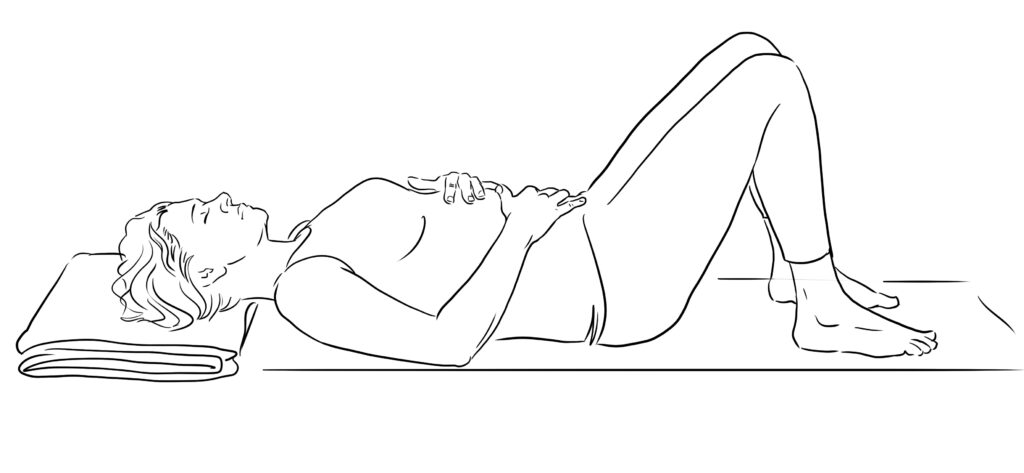

Diaphragmatic breathing

Poor breathing patterns can restrict the diaphragm as it does not usually receive the oxygen or blood flow to fully function. This can lead to digestive issues. Encouraging nasal breath over time will improve this so that ingrained tension can release over time.

- Lie in Constructive Rest Position (CRP) or with the legs raised on the seat of a chair so that the belly is soft and receptive

- With one hand on your lower ribs, the other on your belly, tune inwards to notice which moves first when you inhale and which moves most

- Observe whether you tend to hold the belly, ‘suck it all in’. It may take a psychological as well as physical ‘letting go’ in this region. Allow full exhalations to allow any emotional effects this may bring up

- Once settled, check the belly is easefully moving up and down as you breathe (a book or a bolster on the belly can add some resistance and feedback to help foster this awareness

For a deeper, theoretical and practical dive into respiratory, immune and digestive health through the lens of therapeutic yoga practices, see the books Yoga & Somatics for Immune & Respiratory Health and Yoga Therapy for Digestive Health