Language is  powerful, as is pain. Both can be forceful motivators of behavioural change. Spoken language can be interpreted in many ways. Sometimes we even question whether words mean what we think they mean. Pain can be the same. We wonder whether pain really is intended to “get us to stop or change our behaviour”. We might also wonder “exactly what is it that I am supposed to change? Maybe the change I need to make is to stop responding this way to my pain!”

powerful, as is pain. Both can be forceful motivators of behavioural change. Spoken language can be interpreted in many ways. Sometimes we even question whether words mean what we think they mean. Pain can be the same. We wonder whether pain really is intended to “get us to stop or change our behaviour”. We might also wonder “exactly what is it that I am supposed to change? Maybe the change I need to make is to stop responding this way to my pain!”

As a yoga teacher, leading groups in asana requires instructions that will keep your students safe. As such, cognitive contemplations such as the above are not well-suited as part of an asana practice dialogue. We use language that guides our students to be aware of what is happening in the present moment. We guide them to find the right challenge so they can explore preconceived notions, all the while staying present with, and not ignoring what’s happening now. We use language that provides options for change. “What would happen if you changed the way you are breathing right now?” “Or what you are thinking?” “Or if you let go of some of the aversion to the emotions or tension that you are feeling in your body right now?” In other words, we use language that encourages awareness and language that encourages self-regulation – often of body, breath, thoughts and emotions. Note that this language of awareness is not the same as asking a student to be aware “as the first step to change”. This is language that focuses on awareness as important in and of itself.

Science tells us that certain language is appropriate for injury prevention, as well as when a student is experiencing pain during asana. Yet it’s not always easy to translate science into our implicit and explicit messages as a yoga teacher. As an example, we believe that pain is one way that the body protects us. It’s not the only way. Other protective mechanisms include alterations in breathing, gripping of protective muscles, sensations of stiffness, instability or fatigue, thoughts of danger, and worry that we will regret this activity later. When we move, the first increase in any protective mechanism that we experience is never tissue damage. Rather, what we experience is a message something like “Maybe this is just enough for now.”

Imagine your student has spent their life doing their best to ignore the subtle sensations of their body, or your student is having trouble experiencing the subtle sensations of self because the pain is so ‘loud’. Maybe your student has been told that the best pain self-management technique is distraction. To keep these students safer, encouraging awareness becomes vital.

The language of yoga allows us to avoid turning our asana classes into ‘explain pain’ educational sessions. We can use the language of yoga to teach pain care. Our language guides students to spend more time being present to internal experiences during asana practice, to become aware of more and more subtle experiences, and to practice awareness from that place in which we can witness pain and other protective mechanisms. With this language we open the door for the student to explore their pain, and to become more discerning.

Scientists including Lorimer Moseley tell us that pain is not a tissue-health meter. This does not mean that pain has nothing to do with the body tissues. It means that our pain is impacted by every aspect of our existence, and by all the evidence of safety and of danger. Knowing this, a yoga teacher will understand that language that increases evidence of danger will potentially increase pain, and that the opposite is also true. Pain can be decreased by increasing the evidence of safety. Words, actions and implicit language that clearly identify pain as something to avoid will increase evidence of danger. To keep students safe we might talk about protecting joints. When a student says there is pain in asana, we might suggest an alternative posture. This language can inadvertently increase evidence of danger. So, to keep our students safe, what options do we have?

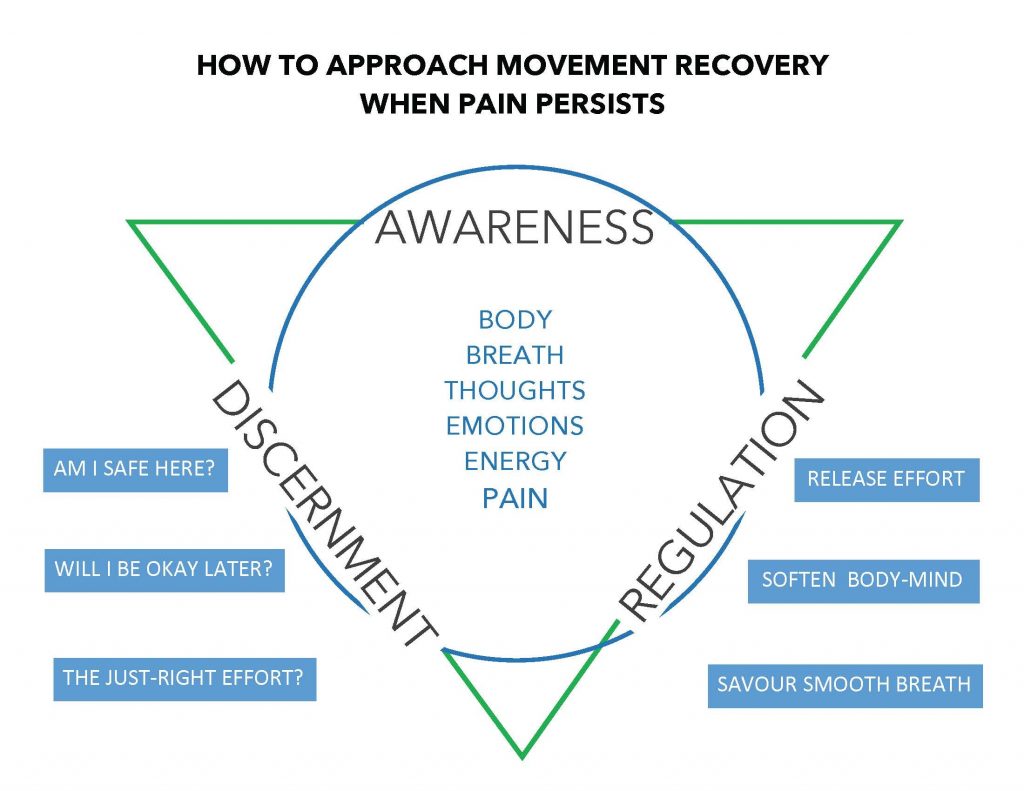

When we focus our language on awareness, on self-regulation and on discernment, our students can find a powerful method of keeping themselves safe, and a path towards knowing how much to move when there is pain (or an increase in any other protective mechanism) during asana practice.

- When we improve our skill in awareness, we can notice when our breath, body, thoughts and emotions are not calm. And as we all have experienced, the act of noticing is at times all that is needed to bring greater evidence of safety.

- When we improve our skill in self-regulation, we create greater capacity at increasing evidence of safety.

- When we explore pain, and other protective mechanisms during movement, and when we spend more time noticing connections between these different mechanisms, then we become more discerning. We gain clarity, and over time can better predict which pains are okay and which ones might leave us regretting the asana later.

Our words, and the actions of our students are powerful educational processes, just as pain can be. When unexplored by yoga teachers, our language can unintentionally foster fear and activity-avoidance. Pain science provides us with greater understanding through which we can evolve the language of asana instruction. Myths and misconceptions can be challenged, allowing the yoga teacher to know that language encouraging awareness, self-regulation and discernment is a powerful tool with which to keep students safe, and to approach pain during asana.

If you have not done so already, re-read this article, making note of any myths or misconceptions you think were discussed.

Then consider this. When a student tells you that they have pain during asana, you now how more options. Asking the student to modify their asana is not the only answer, yet is a perfectly great approach – as long as your complete dialogue with the student doesn’t promote the misconception that pain equals damage.

Pain is both complex and not an accurate indicator of tissue health. As such, the language we use to keep our students’ bodies safe and with which to approach asana when there is pain is the language of yoga that encourages awareness, regulation and discernment.

In other words, the language of love.

Yoga and Science in Pain Care

Treating the Person in Pain

Edited by Neil Pearson, Shelly Prosko and Marlysa Sullivan.

This book takes an integrated approach to pain rehabilitation and combines pain science, rehabilitation and yoga with evidence-based approaches from respected contributors. They demonstrate how to integrate the concepts, philosophies and practices of yoga and pain science in working with people in pain. An essential and often overlooked part of pain rehabilitation is listening to, working with, learning from, and validating the person in pain’s lived experience. Read more